Date Opened: September 1939

Date Closed: June 1946

Capacity: 725

Type of POW:

– Civilian Internees and Enemy Merchant Seamen (September 1939 to July 1941)

– Enemy Merchant Seamen (November 1941 to July 1944)

– Combatant Officers (July 1944 to June 1946)

Description:

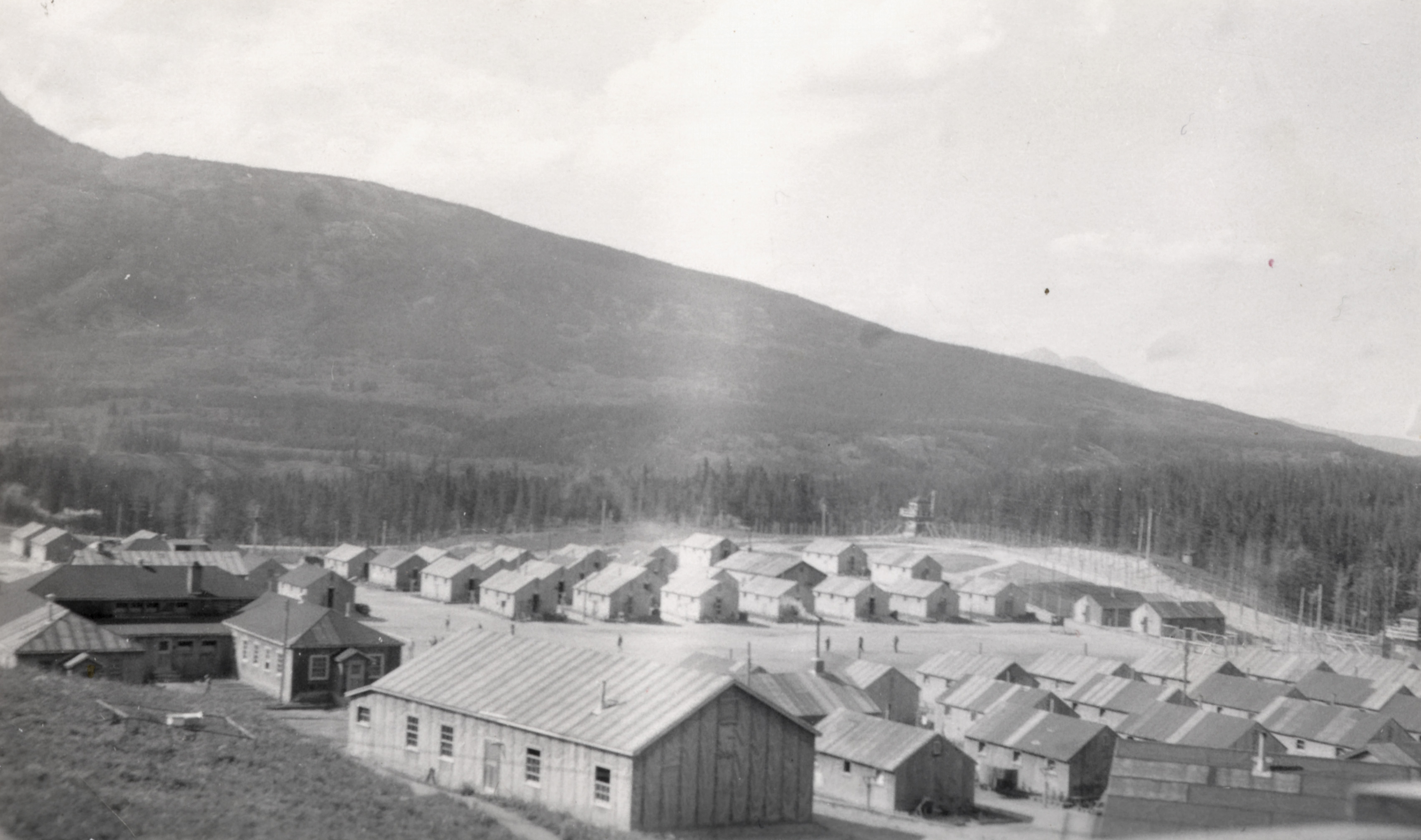

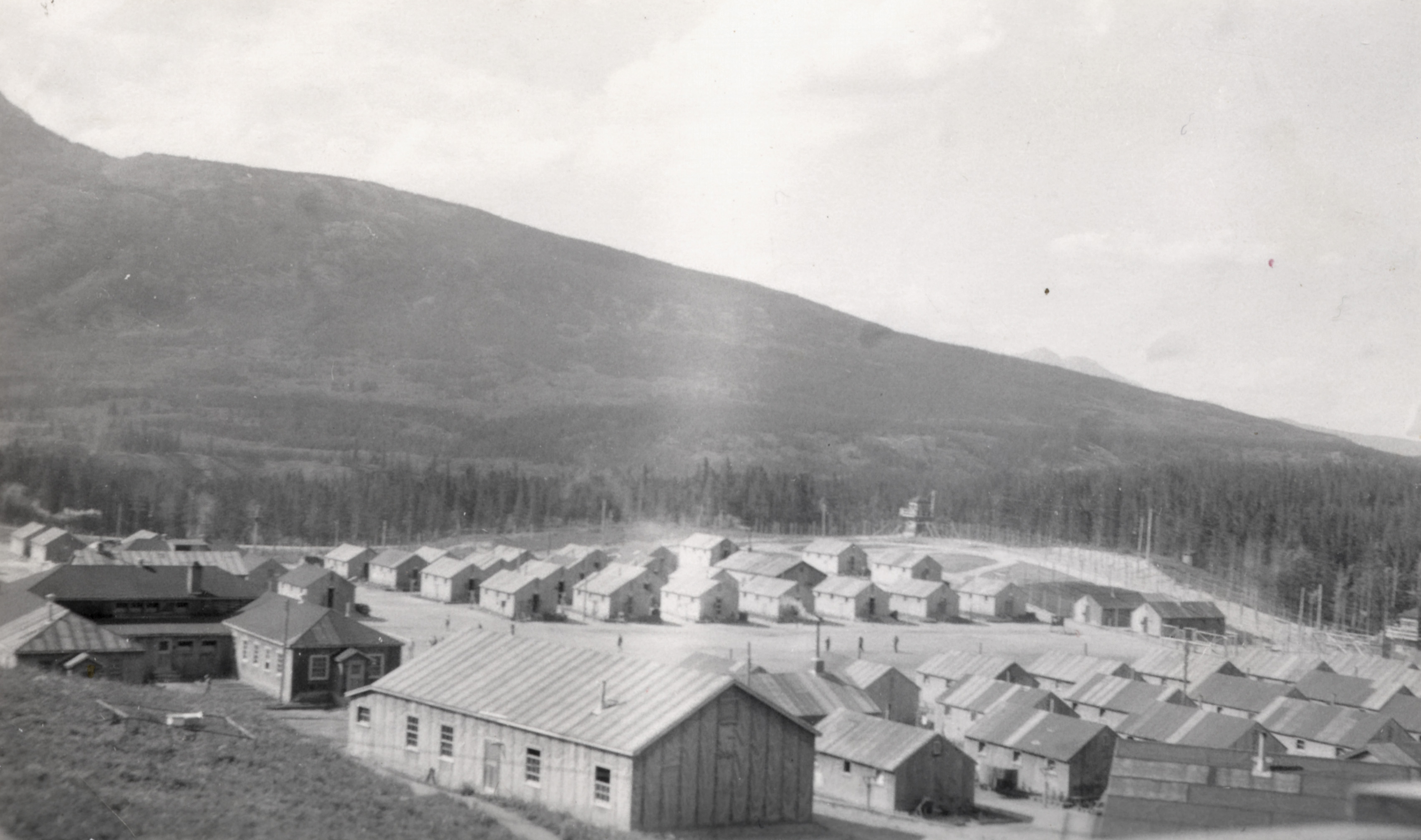

Camp 130 is situated in the heart of the Rocky Mountains in one of the most romantic settings imaginable. Huge peaks emerge out of the dense forest covering the lower slopes. Occasional falls of new snow have put white patches here and there, accentuating outlines and making them even more dynamic, but the colourful rocks still contrast vividly with the darker green of the trees and the clear blue of the sky.

“Camp 130,” n.d., Streight FOnds, Archives of Manitoba.

Canada’s first internment camp of the Second World War, Camp K (Kananaskis) accepted its first internees in September 1939. Originally established as the Kananaskis Forest Experiment Station in 1934, the site was repurposed by the Department of National Defence as an unemployment relief camp until 1936, at which point it was abandoned. As war loomed overseas, the site’s relatively remote location and facilities caught the attention of military authorities looking for sites suitable for internment camps.

Days after the German army invaded Poland, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) began arresting and detaining known and suspected enemy sympathizers in Canada as the Department of National Defence rapidly converted the Kananaskis Experiment Station into an internment camp. Barbed wire fences, four guard towers, and new buildings were erected in days, just in time for Camp K to accept its first internees on September 8, 1939 – two days before Canada even joined the war.

Over the following months, hundreds more internees were transferred to Kananaskis, the majority coming from towns and cities in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. With the opening of Camp P (Petawawa), the number of internees from Eastern Canada dropped significantly as authorities elected to use Kananaskis for internees from Western Canada.

Although the camp’s location was picturesque, the surroundings provided little recompense to the prisoners. Internees were housed in the relief camp’s quarters, with each building housing about ten internees, but the expediency of their internment meant that few recreation opportunities were immediately available. Films were shown once a week – thanks to a prisoners’ personal projector – and the camp library was slowly growing. Several prisoners engaged themselves in making handicrafts to sell as souvenirs in the guard canteen.

Most turned to work to fill their time. Several paid opportunities were made available to the internees, including improving the enclosure parade square, building additional huts, extending the enclosure, planting grass and flowers, and cutting fuelwood.

Over the next year, some internees were released on parole as an investigation board cleared them of any suspicions. Those not so lucky were to remain behind barbed wire for the foreseeable future but their time at Kananaskis soon came to an end. In July 1941, the camp was emptied, with 538 internees transferred to Camp B (Fredericton) and another 175 to Camp P (Petawawa).

The Kananaskis camp – now renamed Camp 130 – reopened in November 1941 with the arrival of 500 German Enemy Merchant Seamen (EMS) transferred from Camp R at Red Rock.

As in most camps, football (soccer) proved the most popular sport and the EMS put together ten teams that regularly competed against one another. The prisoners also played tennis and held athletic competitions during the summer. In the winter months, the prisoners converted the football field into a skating rink and, thanks to equipment donations from the YMCA, played ice sports. Thanks to the camp’s small gymnasium, gymnastics, boxing, wrestling, acrobatics, and table tennis were enjoyed year-round.

As the war dragged on, some of the prisoners looked to the future and took opportunities to advance their education in the hopes of finding better work after the war. As of October 1943, the camp’s forty-two teachers offered courses on eighty-nine subjects including Algebra, Geometry, Maritime Law, Physics, Engineering, Morse code, as well as English, French, Spanish, and Italian – all in varying levels of proficiency.

The EMS eventually assembled a twenty-one piece brass band (apparently one of the best in Canada’s POW camps), a twenty-two piece “Salon Orchestra” (Streichorchester), and a string orchestra. These bands and orchestras held regular performances year round, with the brass band performing every Saturday during the Summer.

Many of the internees were talented craftsmen and produced an array of handicrafts. While these items were generally traded amongst themselves as souvenirs, authorities opened the sale of art and handicraft to camp staff and the guards in January 1944. Ships in bottles, desk sets, model ships, cigarette boxes, and smoking sets were all sold through organized channels, with the proceeds being credited to the prisoners’ accounts.

Able-bodied men were permitted to volunteer for working parties to cut fuelwood outside the camp and many took the opportunity for a brief respite from their barbed wire confines. After Canada approved the employment of POWs in labour projects, Camp 130 became a primary provider of labour to the farm hostel project at Brooks, Alberta. Selected volunteers were moved to Brooks where they either worked as general farm hands on a daily basis from the hostel or lived with the farmers and their families. By June 1944, almost 200 POWs from Camp 130 were employed in the Brooks area.

In mid-1944, a decreasing number of civilian internees in custody and the pending arrival of POWs captured from Normandy prompted authorities to reclassify Camp 130 as a camp for combatant officers. Those working at Brooks remained on the farms but the internees in Camp 130 were transferred to Camp 23 (Monteith) in July 1944.

The departure of the EMS was quickly followed by the arrival of combatant officers transferred from the United Kingdom – the majority of which had only recently been captured in the weeks following the D-Day landings – and a small number of other ranks to serve as orderlies and to assist with the camp’s day-to-day operations.

As part of Canada’s attempt to classify and segregate POWs according to their political opinions, Camp 130 became a camp for POWs classified as “Black,” or pro-Nazi. Those not fitting this description were transferred to Camp 135 (Wainwright) and replaced by prisoners from Camp 20 (Gravenhurst), Camp 30 (Bowmanville), and Camp 44 (Grande Ligne), the latter including members of the “Hari-Kari Club.”

The recent arrivals at Camp 130 picked up many of the activities that they had left behind in their respective camps. An orchestra was formed under the direction of Oblt. Dr. Heinz Brandes, formerly the orchestra director at Camp 44. Professors and educators offered courses in Agricultural, Mechanical Engineering, Commerce, Law, English, Japanese, Spanish, French, Italian, and Russian while other students took or continued correspondence courses offered through the University of Saskatchewan.

We are awakened each morning at seven o’clock when we proceed to the ablution room. After this we go to breakfast and on our return, make our beds. At nine o’clock we are counted. Everybody must appear for this and the ceremony takes about ten minutes. After the count, we are free to do as we please; there are classes in various languages, and in such things as agriculture, law, etc.. And of course, there are sports, wood carving, and such like things. We have lunch at mid-day; the meal takes about half an hour. Then, the library and Canteen open; at the latter we can get what we need. The afternoons are spent in a similar fashion, and at five o’clock there is a second count.

Excerpt of Letter from Alfred Kuehn to His wife, January 1945 From “Intelligence Report, January 1945,” HQS 7236-94-6-130 – T.E.A. – Intelligence Reports – Seebe, C5416, RG24, LAC.

In contrast to other camps, handball became the most popular game in camp. While some football (soccer) was played by other ranks, the officers expressed little interest in the sport for it required more skill and they hoped to avoid any embarrassment in front of the other ranks. Others busied themselves with boxing, badminton, tennis, and, in the winter, hockey. Camp staff also permitted the officers parole walks around the camp area and, in the summer of 1945, swimming parties frequented the the Kananaskis River for a cold, but welcome, swim.

In Fall 1945, prisoners were offered a work opportunity to clear brush on the site of what is now the Barrier Lake Damn. The prisoners worked on parole, with groups working four-hour shifts for $0.50 per eight-hour day. While the increased work led to a decrease in sports, music, and theatre, the opportunity to leave the barbed wire confines of the camp was often appreciated.

Re-education and de-Nazification made relatively little progress at Camp 130, in part due to some of the senior officers’ opposition towards cooperation with the Canadians. While some prisoners were more amenable to re-education attempts, much of the camp’s population remain categorized as pro-Nazi through early 1946.

In June 1946, the prisoners at Camp 130 were transferred to the United Kingdom for their eventual repatriation and the camp closed shortly after. The site returned to its prewar purpose as a forestry research station and it is now occupied by the University of Calgary’s Barrier Lake Field Station. Many of the buildings and infrastructure have since been removed but one guard tower was relocated to a nearby mountain and used as a forest fire lookout after the war. This tower has survived and was returned to the site where it can be seen today. A log cabin occupied by the Camp Commandant can also still be found at the site near a monument honouring the Veterans’ Guard of Canada.

Location:

Pictures: