Date Opened: September 1939

Date Closed: April 1946

Capacity: 800

Type of POW:

– German and Italian Civilian Internees (September 1939 to July 1942)

– Japanese-Canadian Internees (April 1942 to July 1942)

– Enemy Merchant Seamen (August 1942 to January 1944)

– Combatant Other Ranks (February 1944 to March 1946)

Description:

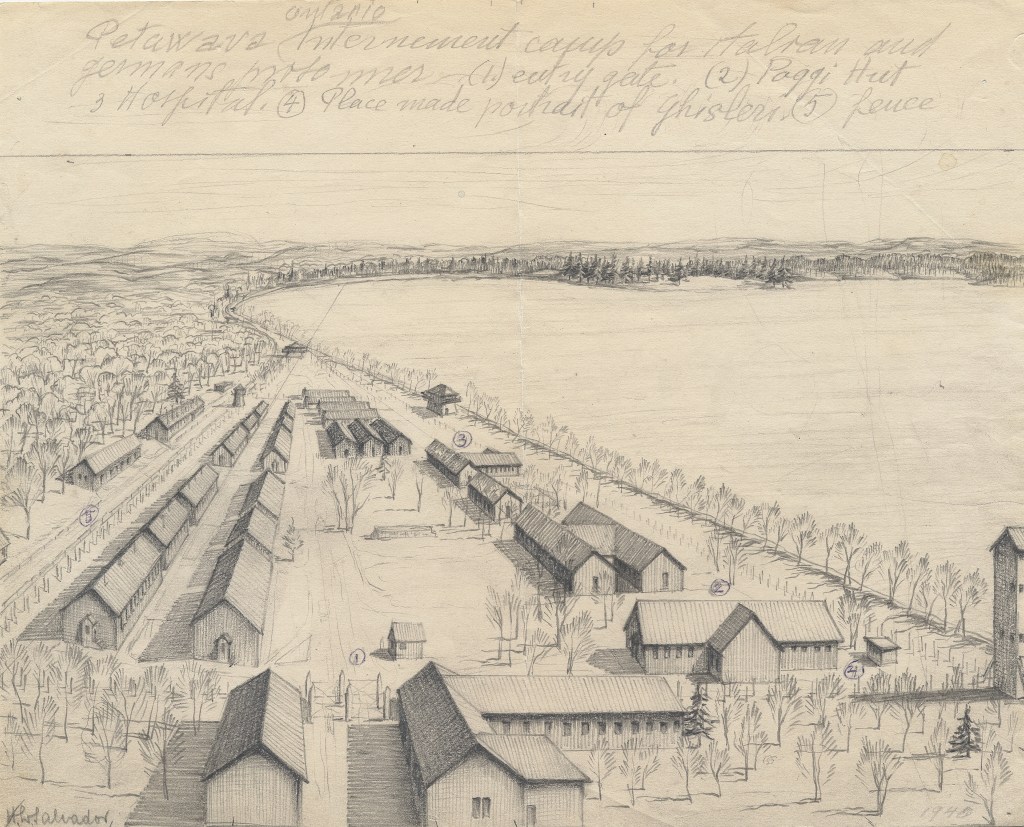

“Petawawa Internment Camp ’33’ is situated in the heart of a wild bush country, approximately thirteen miles from Petawawa Military Camp and seven miles inland from Trans-Canada Highway No. 17, on the North Shore of Centre Lake. The surrounding landscape is very picturesque, indeed, magnificent scenery throughout. The country is dotted with lakes of all shapes and sizes, teeming with fish of all kinds, chiefly small mouth bass, lake trout and maskinonge. The world-renown Algonquin Park, the fisherman’s paradise is within walking distance.”

Lt. B.A. Pickel, Untitled Report, January 6, 1945, _____, C5416, RG24, LAC.

When war broke out in September 1939, the RCMP began rounding up known and suspected pro-Nazis living in Canada while the Department of National Defence began preparing internment camps to house them. The first camp, Camp K at Kananaskis, accepted its first internees on September 8, 1939, but it was quickly decided to divide the country’s internees between two camps; those from Western Canada were to go to Camp K and those in Eastern Canada would go to a new camp, Camp P at Petawawa.

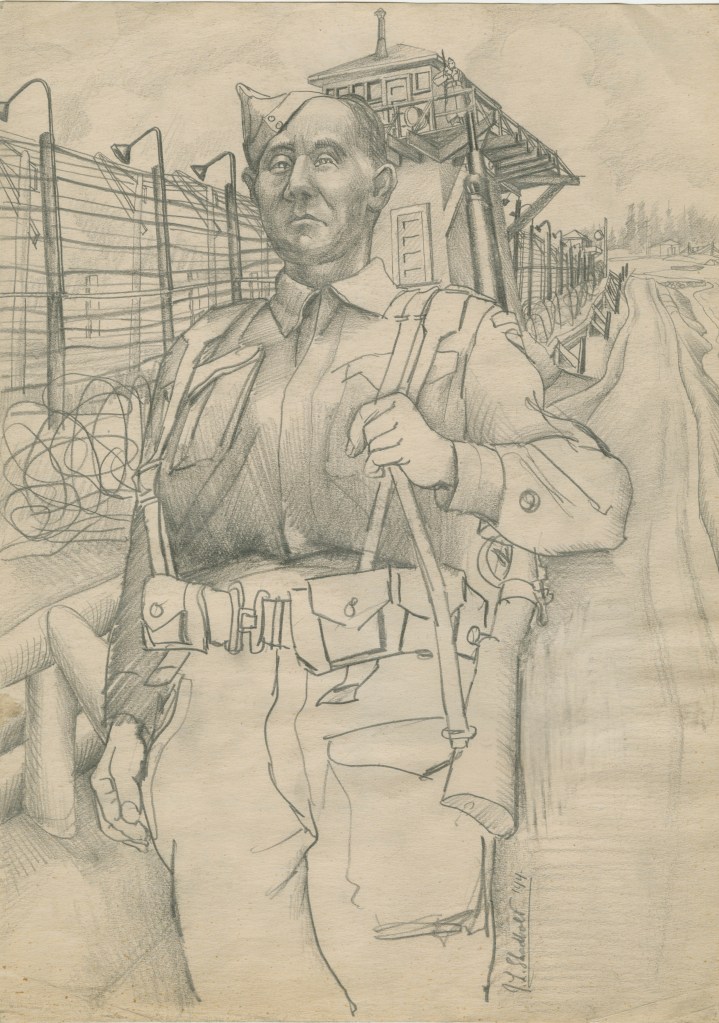

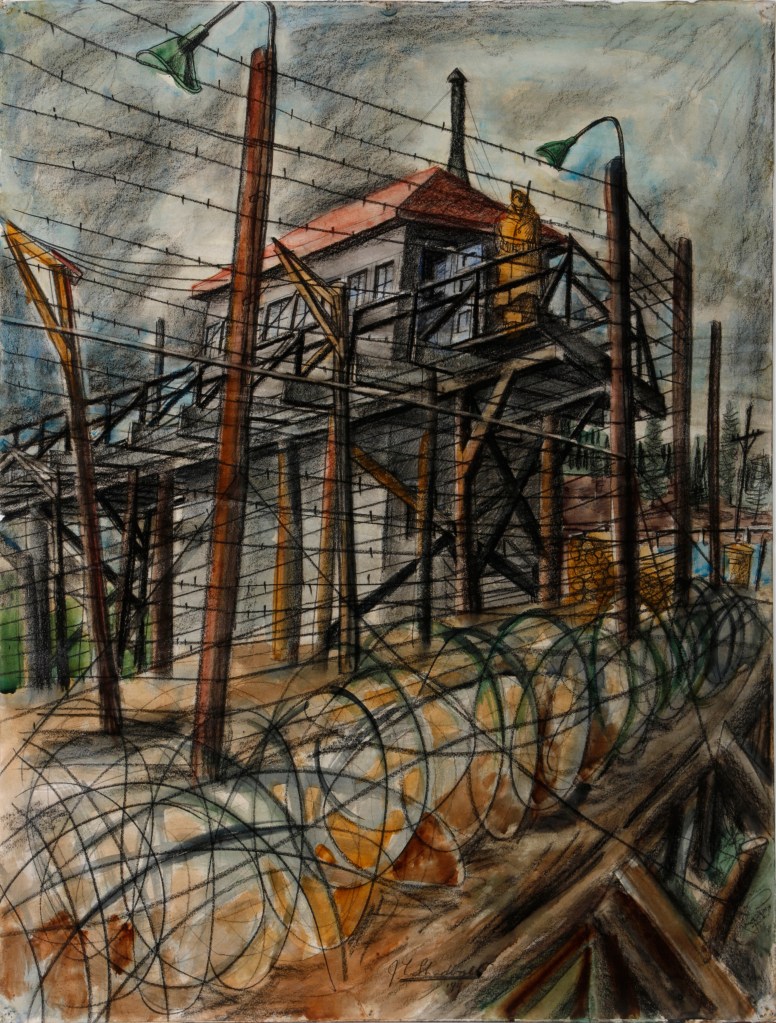

The location chosen for Camp P was a government Forest Experimental Station on the northern shore of Centre Lake, some fifteen kilometers from Petawawa’s military training camp. Existing facilities were quickly converted, additional buildings constructed and barbed wire fences and four guard towers erected around the new enclosure.

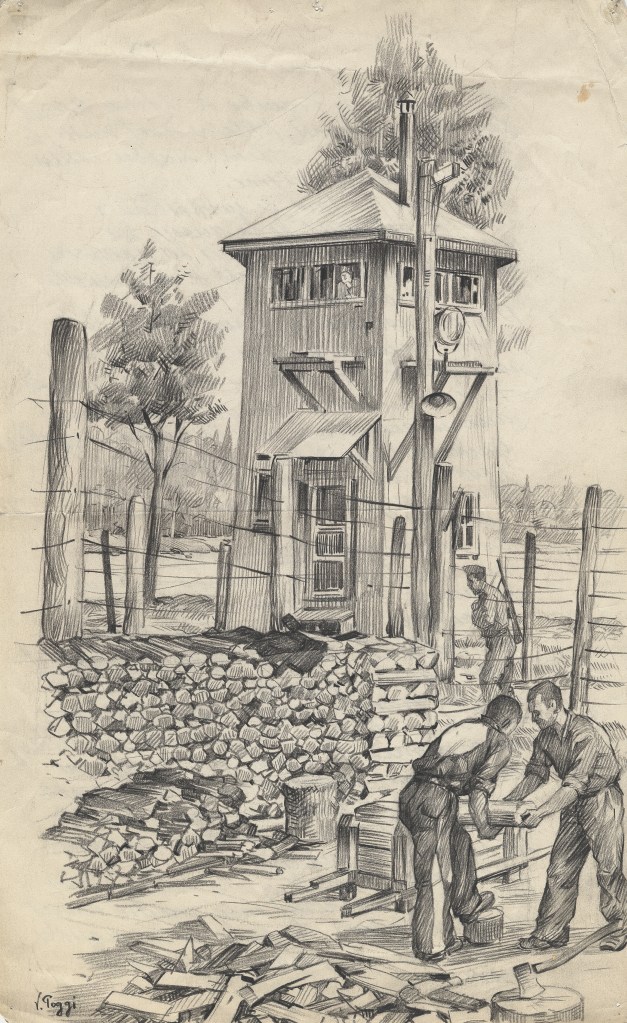

The first internees arrived from the Fort Henry Receiving Station in late September and they were soon joined by internees from the Quebec Citadel and other receiving stations across Eastern Canada. With limited facilities and internment policies rooted in the First World War, recreation was quite limited – at least initially – at Camp P. Instead, authorities focused on providing prisoners with work, believing it would improve both the prisoners’ morale and health. Many internees found work erecting additional barracks and buildings in and outside the enclosure while others cut fuelwood, cleared trees, spread gravel along forestry roads, and worked in general maintenance.

Italy’s declaration of war in June 1940 saw the arrival of Italian internees in Petawawa as authorities began rounding up known and suspected pro-fascist Italian-Canadians. Over the coming year-and-a-half, many internees in Camp P – later renamed Camp 33 – were released conditionally as authorities determined they posed little or no security risk. Those remaining in camp by April 1942 were, however, joined by groups of Japanese-Canadian internees transferred from Camp 130 (Kananaskis) and British Columbia.

In July 1942, Camp 33 was re-designated to hold Enemy Merchant Seamen. The Japanese-Canadian internees were moved to Camp 101 (Angler) and the majority of the German and Italian internees to Camp 70 (Fredericton). The camp did not remain empty for long as the internees were soon replaced by 750 German Merchant Seamen transferred from India.

As in other camps in Canada, the EMS set about improving the recreational and educational opportunities in camp. Educational courses helped prisoners pass the time and, by mid-1943, almost every POW in camp was engaged in some form of coursework. Some resumed coursework interrupted by the war while others took the opportunity to advance their technical training. Studying subjects like navigation, engineering, mathematics, English, Spanish, and French would – they hoped – ensure they could find work after the war.

Thanks to the help of the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA, the prisoners put together one band by 1943 consisting of a piano, bass violin, viola, clarinet, zither, cello, drum-port, three accordions, three guitars, and four violins. In-camp entertainment was also provided by a sixty-man theatrical group which held monthly performances for their comrades. Prisoners also had access to a football (soccer field) in the enclosure and they flooded it in the winter to turn it into an ice rink for skating and hockey.

In January 1944, another reorganization of internment camps saw the transfer of the EMS in Camp 33 to Camp 23 (Monteith). The camp was then re-designated to hold combatant other ranks, with some 650 POWs arriving from the United Kingdom in February 1944. The combatants soon picked up where the EMS left off and busied themselves with courses, sports, and work.

Football (soccer) remained the most popular sport in the summer and teams from each hut competed against each other in a competitive league. Prisoners also played handball and fistball, boxed, took parole walks around the camp area, and swam in Centre Lake. In the winter, table tennis, skating, and hockey filled many prisoners’ days.

By Summer 1945, most of the POWs in camp were employed in some form of work. This included clearing trees for a hydro line, building roads and clearing ranges at the Petawawa Military Camp, and, most notably, building huts and working as general labourers to support was to become Chalk River Laboratories, a Canadian nuclear research facility and the first nuclear reactor outside the United States.

In 1945, the camp became a “Grey” camp for combatant other ranks. Whereas “Black” referred to pro-Nazis and “White” to anti-Nazis, “Grey” included all those in between. Canadian authorities began dismantling Nazi control, introducing a democratic election for the position of Camp Spokesman and transferring pro-Nazis POWs to Camp 100. The prisoners also began publishing their own newspaper, Bruecke zur Heimat, providing them with opportunity to publish their opinions of the war, their internment, and whatever else they wanted, so long as it wasn’t deemed pro-Nazi propaganda. The newspaper proved a valuable asset in disseminating democratic and anti-Nazi views, prompting authorities to transfer the newspaper staff – and, with them, the newspaper itself – to Camp 45 (Sorel) in December 1945.

As Canada began transferring POWs to the United Kingdom in 1946, the POWs at Petawawa were among the first groups to be moved to Halifax. The camp was emptied in early March 1946 and the camp closed the following month.

The buildings were removed from the site after the war. Today, the former camp lies within the boundaries of the Department of National Defence’s Garrison Petawawa and access remains restricted.

Location:

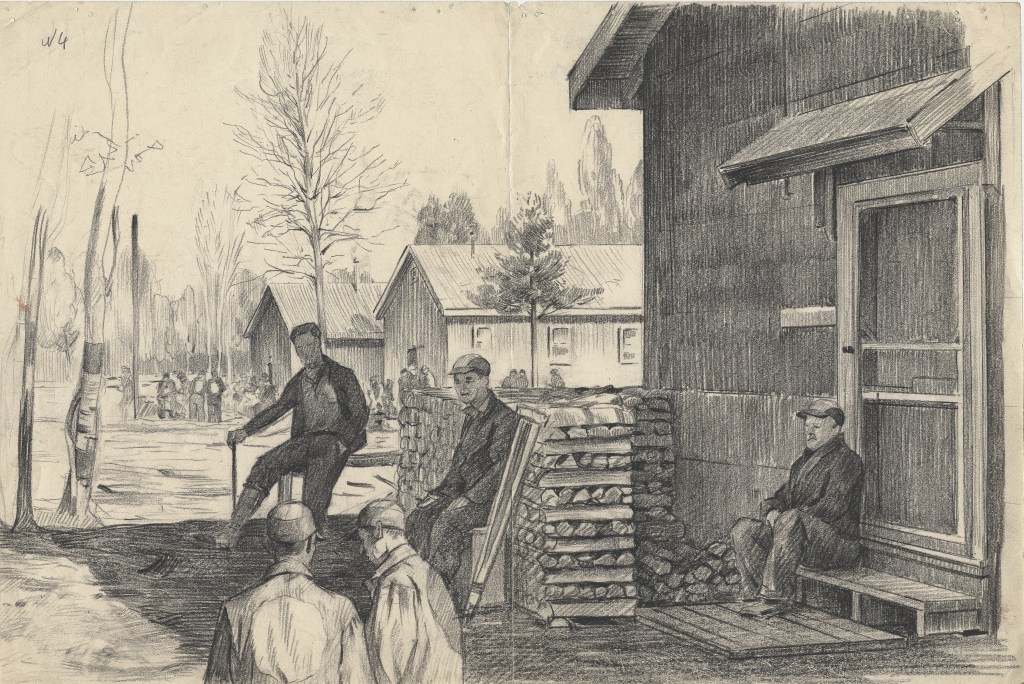

Pictures:

Further Reading:

- Posts about Camp 33 (Petawawa)

- Lucile Chaput. “L’internement au Canada durant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale: le Camp No. 33, 1939-1946,” Études canadiennes / Canadian Studies 81. 2016. 129-147.

- “Italian Canadians as Enemy Aliens: Memories of World War II,” www.italiancanadianww2.ca.