Dates Open:

– January 1941 to December 1943

– September 1944 to May 1946

Capacity: 650

Type of POW:

– Combatant Officers (January to November 1941)

– Enemy Merchant Seamen and Civilian Internees (November 1941 to December 1943)

– Combatant Other Ranks (September 1944 to May 1946)

Description:

Nestled along the Lake Superior coast about halfway between Thunder Bay and Wawa lies Neys Provincial Park. Known for its scenic beauty and long sandy beach, Neys has an important connection to Canada’s internment history for, between 1941 and 1946, it was the site of Prisoner of War Camp 100, initially known as Camp W.

Along with its sister camp, Camp X (later Camp 101) at Angler, Camp W was one of the first two purpose-built internment camps in Canada during the Second World War. Situated on the north shore of Lake Superior, the site of Camp W had been selected largely for its remoteness but it remained close enough to rail lines to regularly receive supplies. Construction of the camp began in the summer of 1940 and the camp was ready for occupation by January 1941. Neys was categorized as an Officers camp while the nearby Angler would hold combatant other ranks.

On January 25, 1941, 241 German officers and 199 other ranks – nearly all Luftwaffe (Air Force) crewman – arrived at Neys. The officers soon complained of sparsely furnished and shared living quarters, which they argued were unsuited for an officers’ camp. With semi-private and far more comfortable accommodations for officers at camps like Camp 20 (Gravenhurst), their complaints were not entirely unjustified and military authorities began looking for more options.

In the meantime, some officers tried making the most of their time at Neys while others turned their attention to escape. The prisoners dug several tunnels through the large snow drifts in the enclosure or, when the ground thawed, under the barracks, but these attempts proved futile. One POW, Lt. Martin Müller, succeeded in escaping the enclosure but was later shot and killed after ignoring a guard’s order to surrender.

The cold weather and exposure to winds blowing off Lake Superior limited outdoor recreation opportunities so music and theatre were popular activities for the first few months. The camp’s sandy soil was ill-suited for football (soccer) but the Commandant did permit supervised swimming and exercise parties along the beach.

In November 1941, the officers were transferred from Neys to the newly-completed Camp 30 (Bowmanville) and almost immediately replaced by German Enemy Merchant Seamen (EMS) and Civilian Internees.

Although the new POWs found the climate to be challenging, the EMS and internees quickly set about improving the camp and soon established skating and hockey rinks in the winter, built a hut for educational courses, and improved the camp library.

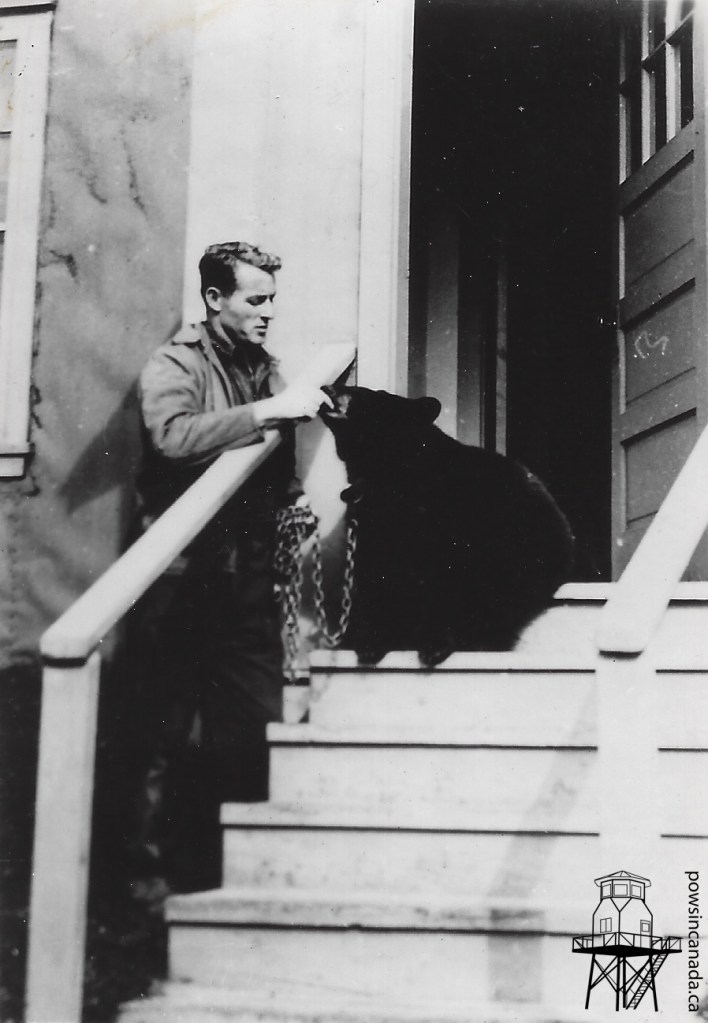

In 1942 or 1943, the POWs at Neys acquired a pet black bear, “Mischka,” who became the camp mascot. Her origins are unknown, but, along with the cats and dogs in camp, appears to have been a beloved companion. Her caretaker, Max Wadephal, kept a careful watch on her and walked her in and around the enclosure.

Following the Canadian government’s approval of POW labour in May 1943, the Pigeon Timber Co. began employing small numbers of POWs in bush work in August. This opportunity for paid work and a brief escape from the enclosure was greatly appreciated by the POWs. The program’s success prompted the company to request 100 POWs to live and work in one of the company’s camps, a request the Department of Labour agreed to.

In late 1943, the Department of National Defence began consolidating EMS at Camp 23 (Monteith), making Camp 100 surplus to its needs. Most of the prisoners were transferred to Monteith, the civilians to Camp 22 (New Toronto), while another small group were transferred to the Pigeon Timber Co. for bushwork. Camp 100 closed – albeit temporarily – in December 1943.

In August 1944, the Department of National Defence reopened Camp 100 for a new purpose: to house the most troublesome pro-Nazi POWs from Camp 132 (Medicine Hat) and Camp 133 (Lethbridge). Pro-Nazis had established internal administrations in most internment camps but now that the war was turning in the Allies’ favour, Canada was tasked with how to classify POWs according to their political beliefs and re-educate pro-Nazis to become democratic citizens in the post-war period.

These Pro-Nazis – categorized as “Blacks” – arrived at Neys in September 1944. Among those transferred from Camp 132 were four POWs who would later be found responsible for murdering a fellow POW immediately prior to their transfer. But also included in the transfer were several Anti-Nazis (Whites) and those in between (Greys).

The pro-Nazis quickly established their own internal administration and, in turn, the Canadians set out to dismantle it. Following the news of Hitler’s death and Germany surrender, Canadian authorities began classifying POWs according to the new PHERUDA system and instituted several new regulations, including the banning of Nazi imagery and portraits of Hitler. Prisoners watched newsreels and documentaries showing the atrocities of the Holocaust and, although many initially dismissed these as enemy propaganda, coverage in newspapers and letters from home prompted some to rethink this. Authorities also introduced democratic elections for Camp Spokesman and encouraged the publication of an camp newspaper in an effort to undercut Nazi influence.

Although authorities did not succeed in converting every Nazi at Neys, there were many successes and, by 1946, Nazi influence was significantly diminished. At this time, the Canadian government began transferring POWs to the United Kingdom for their eventual repatriation and, in late March, the last POWs left Neys.

Following the prisoners’ departure, the Department of Labour briefly used the camp as a hostel to house Japanese-Canadians relocating from British Columbia to Northern Ontario. The Ontario Department of Reform Institutions then purchased the camp in 1947 and repurposed it as an industrial farm employing civilian inmates in woodcutting, road work, and dismantling the former POW camp. In 1965, the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests declared much of the Coldwell Peninsula – including the area once occupied by Camp 100 – as Neys Provincial Park.

Today, red pines have replaced much of the clearing that was once Camp 100. Neys Provincial Park remains a popular camping destination for those traveling along Highway 17 between Thunder Bay and Sault Ste. Marie. Visitors can find a scale model of the camp and more information about the site’s history in the visitor centre while staff provide guided tours during the summer months.

Location:

Pictures:

Further Reading:

- Posts about Camp 100 (Neys)

- O’Hagan, Michael. “Waiting out the War on the Shore of Lake Superior: Camp 100 and Neys Provincial Park.” Ontario History 115, no. 1 (2023): 114–39.

- O’Hagan, Michael. “Waiting Out the War on the Shore of Lake Superior,” Thunder Bay Museum Virtual Lecture. https://vimeo.com/791187355.