Date Opened: July 1940

Date Closed: November 1946

Capacity: 4,000

Type of POW: Civilian Internees, Enemy Merchant Seamen, and Combatant Other Ranks

Description:

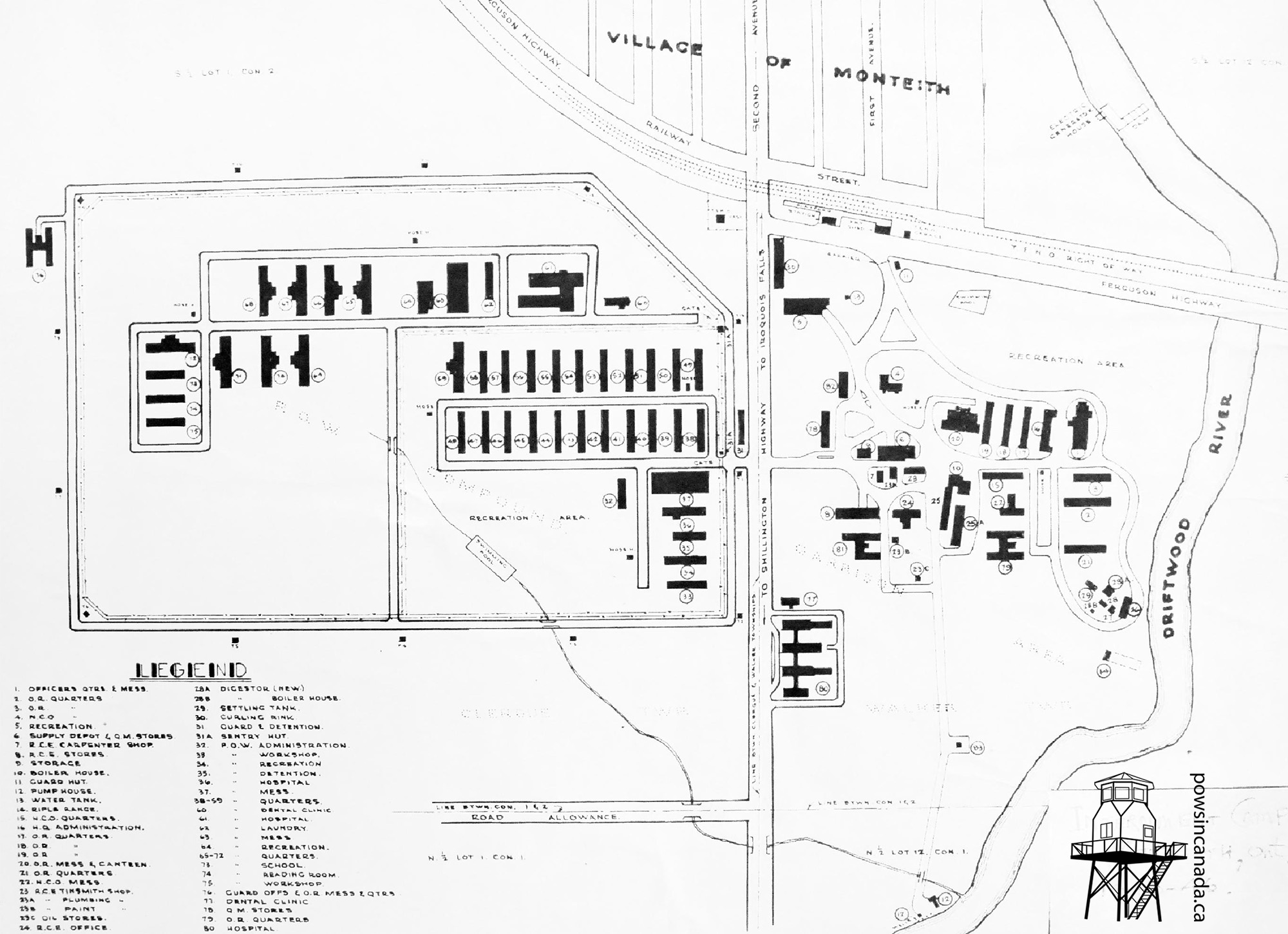

Over a few short years during the Second World War, the village of Monteith in Northern Ontario went from being the site of a small prison reform farm to having the largest internment camp in Ontario and fourth largest in Canada.

When war broke out in 1939, the village of Monteith was the site of a Ontario Government Detention Farm. Here, civilian inmates arrested from larger cities in the province spent part of their sentence learning how to work on a farm, a practice that not only helped boost agricultural production but also provided inmates with useful skills. Its remoteness and existing facilities caught the attention of military authorities and it was identified as a potential location for an internment camp. After Canada agreed to accept prisoners from the United Kingdom, the Department of National Defence took over the Detention Farm in 1940.

Thanks to the site’s existing security measures, few upgrades were required. The camp area was surrounded by two barbed wire fences – with part of the inner fence electrified – and four guard towers. A combination of men from the Ontario Regiment and the Veterans Home Guard were tasked with guarding the camp but the Veterans Home Guard (later renamed the Veterans Guard of Canada) assumed all security responsibilities shortly after the camp’s opening.

The first prisoners – some 501 Category B and C Internees – arrived at Monteith on July 14, 1940, immediately outnumbering the village’s 250 residents. Most of the POWs were housed in the former detention farm facilities but some guards and internees lived in tents until additional buildings were erected later that summer.

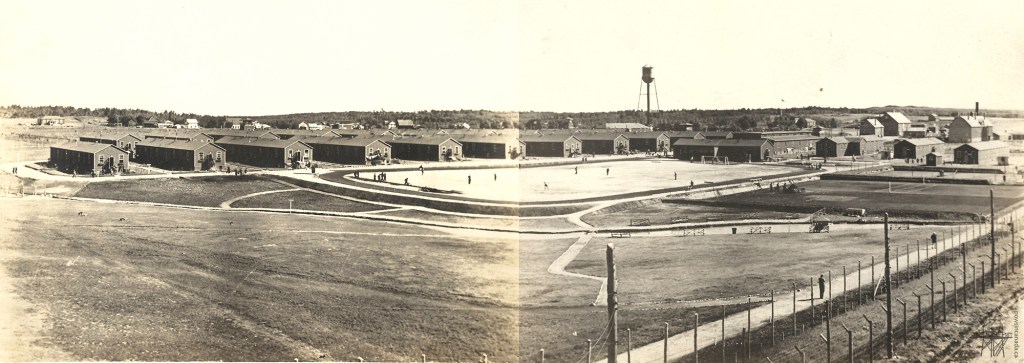

In 1941, Canadian authorities elected to expand Camp Q to a capacity of 1,500 POWs, in part to allow for the transfer of the Enemy Merchant Seamen and civilian internees presently interned in Camp R, which was slated to be closed by the end of the year. The result was that an entirely new compound was built across the road from the original camp. The new buildings included fifteen POW barracks, a hospital, detention barracks, a recreation building, and a library and office as well as separate quarters and messes for the guards.

In the latter half of 1941, Canada began reorganizing its internment camps. The letter designations were dropped in favour of numbers and, as such, Camp Q became Camp 23 in October. As part of the shuffle, Camp 23 was designated to hold combatant other ranks so the roughly 600 civilian internees and EMS in camp were transferred to the recently vacated Camp 100 (Neys) in November.

Some 1,600 combatants were transferred to Monteith by mid-1942 but the pending arrival of POWs from North Africa prompted another significant expansion of Camp 23, this time increasing the camp’s capacity to 4,000 POWs. But rather than just hold combatants, Monteith would now hold combatants and non-combatant prisoners, with the two parties held in separate enclosures. With the additional barracks ready by late 1943, the camp accepted approximately 400 EMS from Camp 22 (New Toronto) and 138 civilian internees from Camp 31 (Fort Henry) in November.

Camp staff encouraged POWs engage in work or in recreational activities as it helped keep them occupied and thereby less likely to escape. As part of this, authorities permitted the prisoners to farm on a plot of land near camp to grow vegetables in 1942. The success of the farm prompted camp staff to expand the operation from twenty-eight acres in 1942 to seventy over the next two years. Prisoners planted and harvested potatoes, turnips, beets, carrots, parsnips, onions, and cabbage on the farm and, inside the enclosure, others tended small vegetable and flower gardens. This work not only helped make the camp a little more self-sufficient, but kept the POWs busy.

The camp’s expansions in 1941 and 1943 included large open areas of land which the POWs converted into recreation grounds, adding their own sports fields with dedicated tennis courts and football (soccer) pitches. Inside, POWs also busied themselves with table tennis, gymnastics, and boxing. Swimming and bathing parties were permitted in the Driftwood River and some took the time to try fishing with hand-made rods. In order to make swimming more accessible, the POWs built their own swimming pool complete with diving board in the enclosure in 1943.

In the winter, prisoners flooded parts of the recreation grounds and converted them into separate skating and hockey rinks. As winter recreation was initially limited, camp staff permitted small groups of fifteen to twenty POWs to leave the enclosure and ski on a nearby hill under the watch of armed guards. Once this practice was discontinued due to security concerns, the POWs simply took matters into their own hands and built their own ski and toboggan hill within the main enclosure.

Thanks to the camp’s size, there were many experienced teachers and professionals who used their experience to develop educational courses. Course subjects ranged widely and many were able to use the courses to advance their professional skills. Seamen were able to take courses on subjects including navigation, ship-building, astronomy, and engineering while other POWs busied themselves taking courses on mathematics, sciences, and languages.

While prisoners were permitted to send and receive mail, isolation from their friends and families took its toll. Many POWs took to pets for companionship and there soon was no shortage cats, dogs, and rabbits within the enclosure. Many were brought with the prisoners from other camps while others wandered in from town or were acquired by guards and camp staff. Most notably, the POWs had two pet black bears, Nellie and Susie (or Suzi). Nellie had been transferred from Camp 20 (Gravenhurst) while Susie’s origins are unknown. The POWs added a dedicated enclosure for the bears within the camp’s main enclosure that included a small cabin.

As of April 1944, the POWs at Camp 23 had assembled a a thirty-five piece orchestra, an eighteen piece dance orchestra, and another thirty-piece orchestra of EMS as well as a 30-piece brass band and a five-piece chamber music group. Gramophone concerts were held several times a month, a theatrical troupe put on performances for their comrades, and movies provided by the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA were shown regularly.

Art and handicraft were also especially popular. Skilled artists like Georg Högel and Hans Krakhofer documented their time behind barbed wire in sketches, portraits, and paintings. Model ships and ships in bottles were also produced in large numbers and the prisoners sold and traded them amongst themselves and later sold them to guards and camp staff in organized sales.

After Canada approved the employment of prisoners of war to help boost the struggling agricultural and logging industries, Camp 23, along with Camp 132 and Camp 133, became one of the primary sources of POW labour for bush camps operated by civilian companies in Northwestern Ontario. Thousands of prisoners from Monteith were sent to bush camps across Ontario as well as farms in Southwestern Ontario in the Summers of 1944, 1945, and 1946.

The camp remained open through 1946 and, as Canada began transferring prisoners to the United Kingdom for their eventual repatriation, Monteith served as a central collection point for POWs returning from bush camps and farm hostels in Ontario and Manitoba. Most of these prisoners spent very little time in Camp 23 before being moved to Halifax for their transfer to the United Kingdom but select volunteers were transferred to hostels to work on farms for the Summer of 1946.

Camp 23 closed in November 1946 and the site was returned to the Ontario Government. The former camp resumed operation as a detention farm in 1947 and most of the buildings were destroyed or relocated to other detention facilities in the following years. Today, fields occupy most of what was the main enclosure of Camp 23 but some of the buildings of the original detention farm, including the water tower, are still in use as part of the Monteith Correctional Complex.

Location:

Labour Projects:

Camp 23 (Monteith) was one of the primary sources of POW labourers. With its relatively central location in Ontario, the camp provided thousands of POWs to bush camps throughout Northwestern Ontario as well as EMS and POWs to farm hostels in Southwestern Ontario.

Pictures:

Further Reading:

- Posts about Camp 23 (Monteith)

- Lanosky, Peter. Barbed Wire, Black Flies, 55° below: The Story of the Monteith, Ontario POW Camp, 1940-1946. Lone Buttle, BC: Lanworth Creative, 2011.