Date Opened: November 1942

Date Closed: December 1946

Capacity: 12,500

Type of POW: Combatant Other Ranks

Description:

By 1942, Allied advances in North Africa had netted thousands of German prisoners of war and, with British authorities wanting to transfer away from the front lines, thousands were sent to Canada. Canadian internment camps, however, were already at capacity so construction of two new, dedicated camps, Camp 132 at Medicine Hat and Camp 133 at Lethbridge, began that summer. As the prisoners began arriving in May, they were first housed in the temporary, tented Camp 133 at Ozada and transferred to Lethbridge once the camp was complete in November 1942.

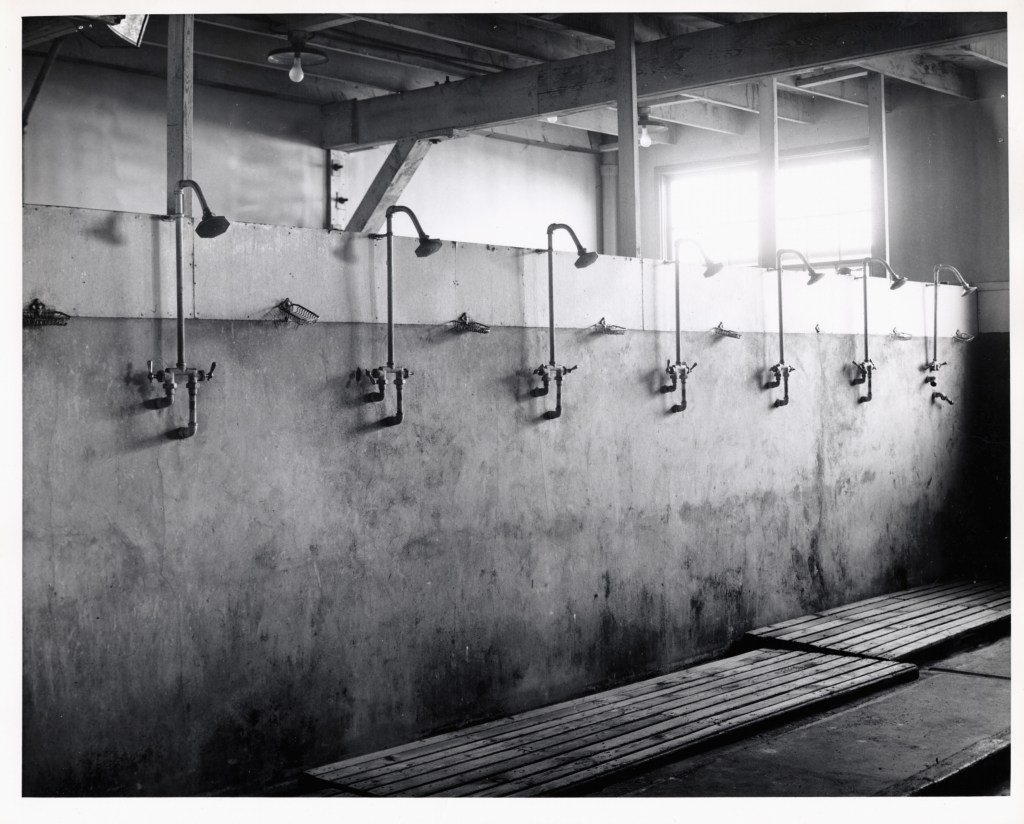

Measuring one square mile, Camp 133 at Lethbridge had a capacity of 12,500 POWs. The main enclosure was surrounded by two layers of barbed wire fences, a warning wire, flood lights and twenty-two guard towers manned by men of the Veterans Guard of Canada. The enclosure was divided into six sections (A, B, C, D, E, and F), each with their own bunkhouses, kitchen and mess hall, workshops, and classroom. Two large recreation halls, used for theatrical and musical performances, gatherings, and funerals, were shared by the sections. The enclosure also included a small hospital and dental clinic, both staffed by POW doctors, dentists, medics, and orderlies. Beyond the barbed wire fences were the guards’ and staff buildings, which included quarters and messes, an administration building, a guardhouse, detention cells, and a larger hospital.

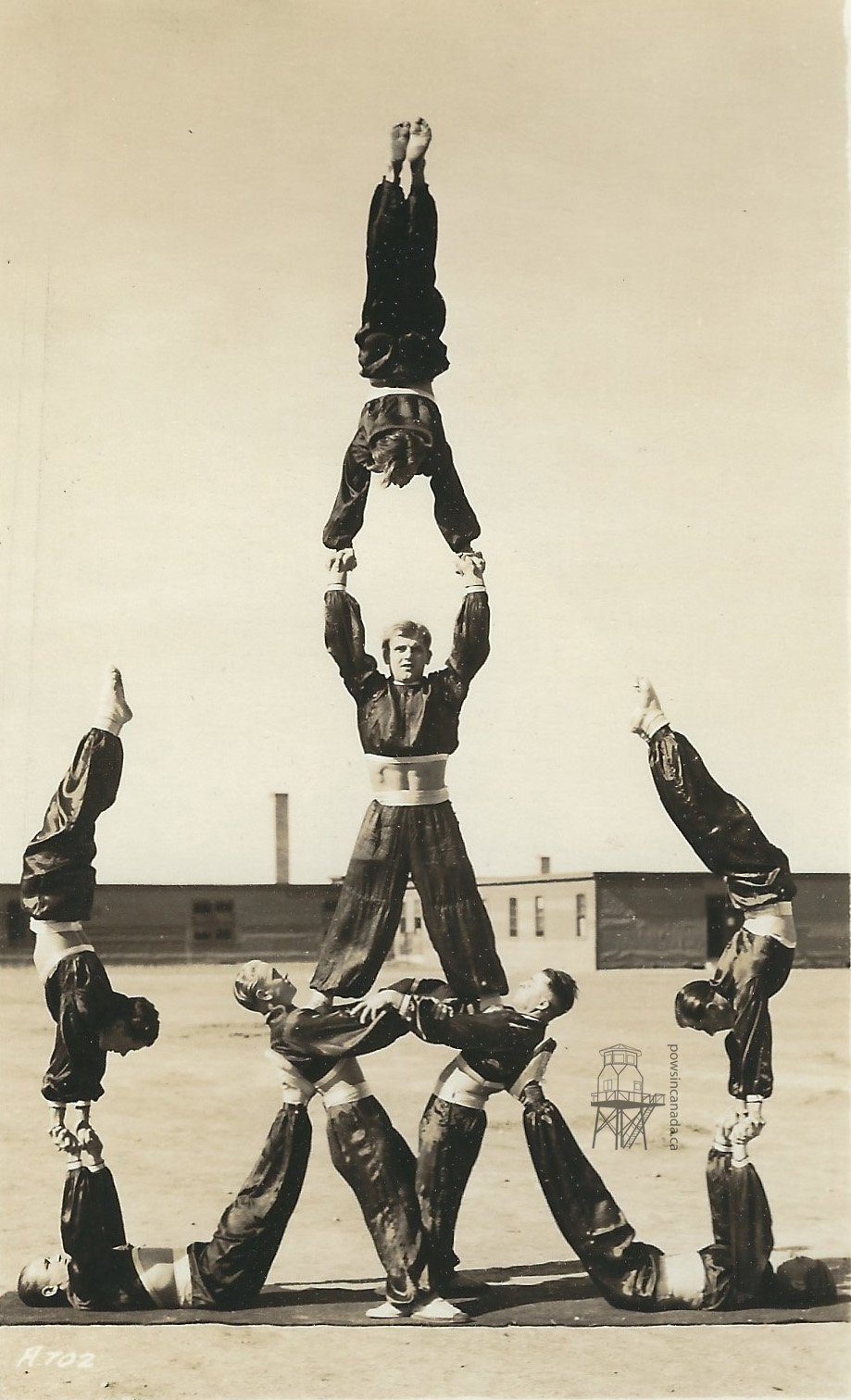

With nothing but time on their hands, the POWs quickly found ways to keep themselves entertained and much of the enclosure grounds were quickly converted to recreation fields. Sports thus became especially popular and important pastimes. Football, or soccer, was the favourite and the POWs assembled several teams and regularly hosted competitions between camp sections. In addition to numerous football fields, the POWs also had seven tennis courts and, in the winter months, three hockey rinks. The camp also included several talented acrobats and gymnasts who trained on parallel and horizontal bars.

Those less athletically-inclined turned to their attention elsewhere. Many prisoners busied themselves planting vegetable and flower gardens, which not only helped supplement their diet and beautify the camp, but also helped keep down the dust that seemed to plague the camp.

Art and handicraft were also especially popular. Talented artists busied themselves painting portraits of their comrades, landscapes, and local flora and fauna or turned the walls of the mess halls into large canvases, decorating them with portraits of famous Germans and scenes from their homeland. Others turned out scale models of tanks, ships, submarines, planes, and trains along with carved animals, busts, and ships-in-bottles.

Those willing to learn attended educational classes hosted by their comrades who had once been professors and teachers. Some 2,000 students were hoping to take courses as of early 1943 and this grew to over 7,000 over the next year. A vast array of subjects were taught within the confines of Camp 133, including law, languages, history, engineering, mathematics, and science.

Prisoners put together two separate orchestras – a fifty-five man symphony orchestra under Johann Onken (as of June 1943) and another thirty-four man orchestra under Hans Singer. Several other small dance bands and musical groups were also established including “Tanzkapelle Matte” under Herbert Matte, “Tanzkapelle Leske” under Herbert Leske, and “Tanzkapelle Schicht” under W. Schicht.

One symphony orchestra of fifty-five pieces conducted by a professional conductor gave a concert for me in the evening in the dining room with an attendance of about 1300 men. This orchestra is as good as, if not better than, many symphony orchestra in our towns. They played jewels from the German classics. Another orchestra is a chamber orchestra with thirty-four instruments and besides they have two dance orchestras and one mandolin and guitar orchestra.

Dr. Jerome Davis, “Report of Work in the Canadian Internment Camps during the Months of February and March 1943,” n.d., B1984-0014/001 (10) – Reports – Boeschenstein and Others 1943. Herman Boeschenstein fonds, University of Toronto ARchives.

In May 1943, the Canadian government approved the use of German prisoners of war in agricultural work. In late May, the first groups of German POWs at Lethbridge were allowed out of the camp under guard to work on nearby fields. The work was primarily centred on the harvesting of sugar beets, although prisoners also assisted in general farm work. For their work, POWs received $0.50 per day. Although many prisoners were employed directly from Camp 133, Canadian authorities elected to establish nine temporary, tented farm hostels surrounding Lethbridge to provide farmers easier access to POW labour. These hostels were located at Barnwell, Iron Springs (Picture Butte), Magrath (Raymond), Stirling, Park Lake, Coaldale, Whiteside, Welling, and Turin.

As labour projects were expanded to include other types of work, Camp 133 was among the largest supplies of POW labour. Thousands of POWs from Lethbridge worked in bush camps in Northwestern Ontario and Alberta as well as farms in Manitoba and Ontario.

Like most internment camps in Canada, pro-Nazis exerted significant control within the enclosure. The pro-Nazis who had exerted power in Angler and Espanola continued their influence in Ozada and Lethbridge, setting up an organized administration within the camps. They ensured Nazism remained strong in the camp and labour projects through lectures and discussions and by censoring news and incoming and outgoing mail. Those who spoke or acted out against Hitler and the Nazis were carefully watched, threatened, or even beaten.

The transfer of known Nazi leaders and troublemakers to Camp 100 (Neys) in September 1944 helped reduce Nazi influence but half the camp were believed to be “Black” (pro-Nazi) by November 1945. Canadian authorities focused their attention on re-education and de-Nazification efforts but many prisoners were transferred to the United Kingdom before the work was complete.

The camp remained open through the Summer of 1946 to provide POW labour to local farms. Shortly after the Canadian government decided to transfer all remaining POWs to the United Kingdom, the last POWs at Lethbridge left for Halifax in December 1946.

No longer needed, the camp was dismantled and, within a few years, most of the buildings were sold for scrap or demolished. Today, the site is occupied by Lethbridge’s industrial area and nothing remains of the camp. A small monument erected by the Lethbridge Historical Society marks the southwest corner of the camp.

Location:

The former camp lies within the area now bordered by 5th Avenue N to the South, 28th Street N to the west, 12th Avenue N to the north, and 39th Street N to the east.

Pictures:

Further Reading:

- Posts about Camp 133 (Lethbridge)

- Fooks, Georgia Green and Lethbridge Historical Society. Prairie Prisoners: POWs in Lethbridge during Two World Conflicts. Lethbridge, AB: Lethbridge Historical Society, 2002.

- Kilford, Christopher R. On the Way! The Military History of Lethbridge, Alberta (1914-1945) and the Untold Story of Ottawa’s Plan to de-Nazify and Democratise German Prisoners of War Held in Lethbridge and Canada during the Second World War. Victoria, BC: Trafford, 2004.