Date Opened: January 1943

Date Closed: May 1946

Capacity: 12,500

Type of POW: Combatant Other Ranks

Description:

Camp 132 at Medicine Hat emerged as a result of the thousands of German soldiers captured in North Africa and the British desire to transfer them further from the front lines. By 1942, Canadian internment camps were at capacity but, with thousands of prisoners now on the way, the Canadian government elected to establish two large purpose-built camps: Camp 132 at Medicine Hat and Camp 133 at Lethbridge. Construction began in Summer 1942 and while its sister camp at Lethbridge opened in December 1942, Camp 132 accepted its first prisoners in January 1943.

Surrounding the enclosure was a single strand of warning wire approximately one foot off the ground. Prisoners were not to cross without this wire without permission as anyone who did so and ignored the guards’ warnings would be fired upon. But the prisoners would also have to then contend with two layers of barbed wire fences, illuminated at night by floodlights, and a series of twenty-two guard towers constantly manned by the Veterans’ Guard of Canada.

The enclosure was essentially a city of its own, with everything the POWs needed housed within. Divided into six sections (A, B, C, D, E, and F), the enclosure was designed to hold 12,500 POWs. Prisoners lived in one of the thirty-six two-story barracks and ate in one of the six mess halls while injured or sick prisoners were treated in a 125-bed hospital run by German POW doctors and orderlies (although serious cases could also be dispatched to a civilian hospital). Each section also had their own workshops and classrooms. Two large recreation halls were shared by the sections and used for theatrical and musical performances, gatherings, and funerals.

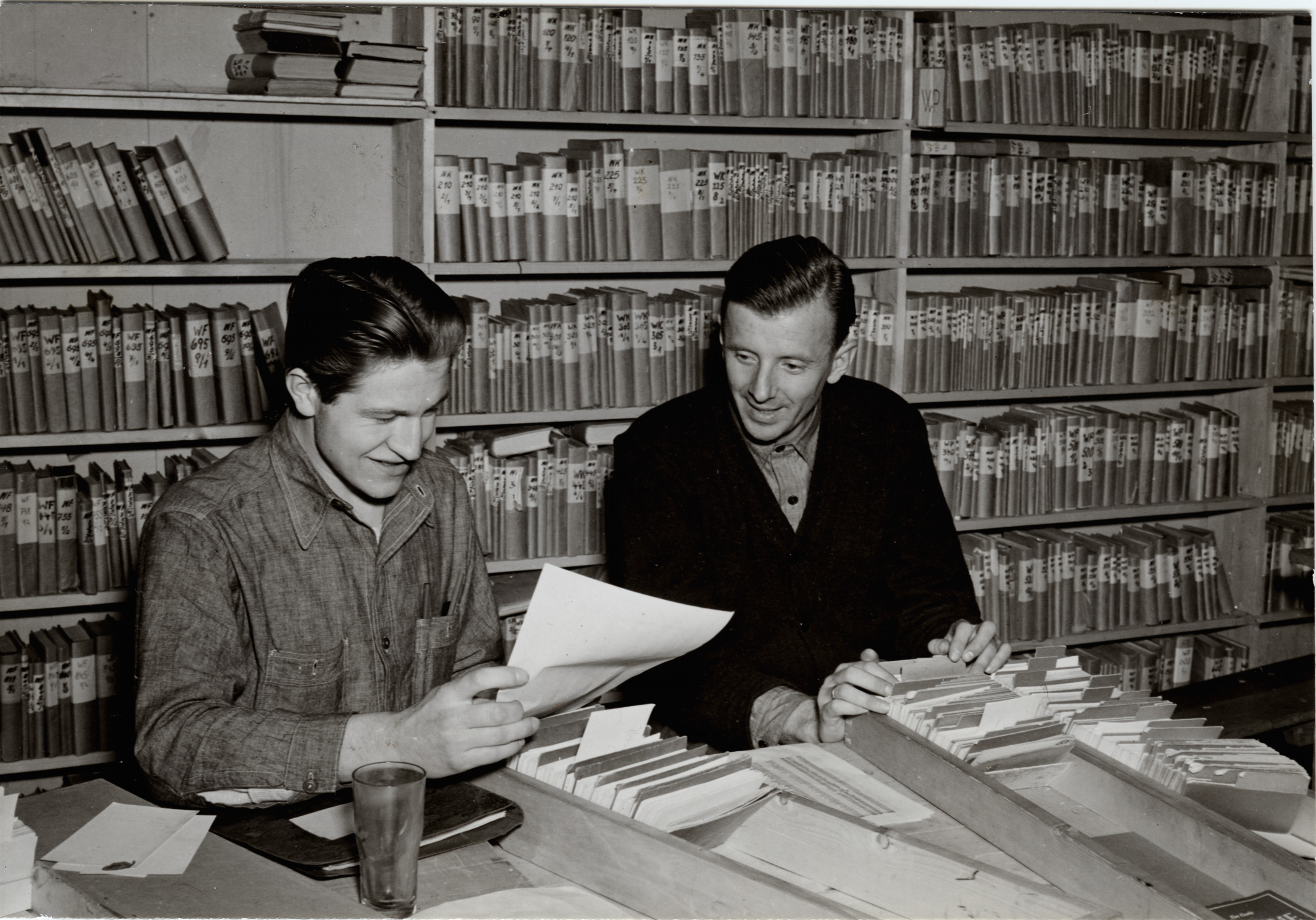

Running a camp of this size required considerable manpower; in October 1944, for example, some 950 Canadian soldiers were involved with guarding and administering the camp. The majority were members of the Veterans’ Guard but personnel also came from the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and Military Intelligence. These men all required their own quarters and messes while an administration building housed the camp commandant and his staff, censors sorted and read incoming and outgoing mail in the postal hut, and quartermaster shops provided the supplies needed to keep everything running smoothly.

With nothing but time on their hands, the prisoners busied themselves in various activities. Some prisoners were employed within the camp to help with the day-to-day operation, but most found themselves without work. Activities were encouraged by Canadian authorities for a busy POW was less likely to cause trouble and therefore less likely to escape. As such, the camp had several lecture halls and workshops. As of mid-1943, some 3,000 of the 5,000 POWs in camp were taking courses in subjects ranging from languages to gardening to the trades. Many POWs also enrolled in correspondence course offered by the University of Saskatchewan, with the prisoners responsible for paying their own course fees.

With many talented artists and artisans in camp, art and handicraft became popular pastimes and POWs busied themselves painting, sketching, carving, and building. Several prisoners even turned the mess hall walls into canvases; one representative of the War Prisoner Aid reported:

…we were taken into a mess hall, bright and airy, with everything spic and span. Instead, however, of the row of floral stencils on one beam, all the beams were decorated and the three walls facing the kitchen were covered with a strip of murals reproducing in colour many of the well-known figures of the German caricaturist humorist, Wilhelm Busch — Max and Moritz, die Fromme Halene, and many others. On the third wall nearest the kitchen the artist — Uffz. Herbert Tauber (260975) from Vienna — he was at work on one of the last scenes of the series. He told me the work had been planned in collaboration with another professional painter in the camp, but that he had executed all the drawings in this particular hall. He was studying art in Vienna, still had four terms to put in and was very pleased at having this opportunity to keep his hand in. The effect of the murals and the other decorations was to make the mess hall much more like a German restaurant, and this emphasis on specifically German features was noticeable in other fields, and tended to become perhaps the outstanding characteristic of the camp.

“Camp 132,” n.d., Archives of Manitoba

Exhibitions were organized for POWs to showcase their art and handicraft, although their market was limited. Prisoners could trade amongst themselves but guards and camp staff were initially forbidden from engaging in any trade or sales with POWs. Fortunately for the POWs, and thanks in part to the War Prisoners Aid of the YMCA, these restrictions were later lifted and guards, staff, and select civilians were permitted to purchase articles from POW exhibitions, with the proceeds being credited to the prisoner’s account.

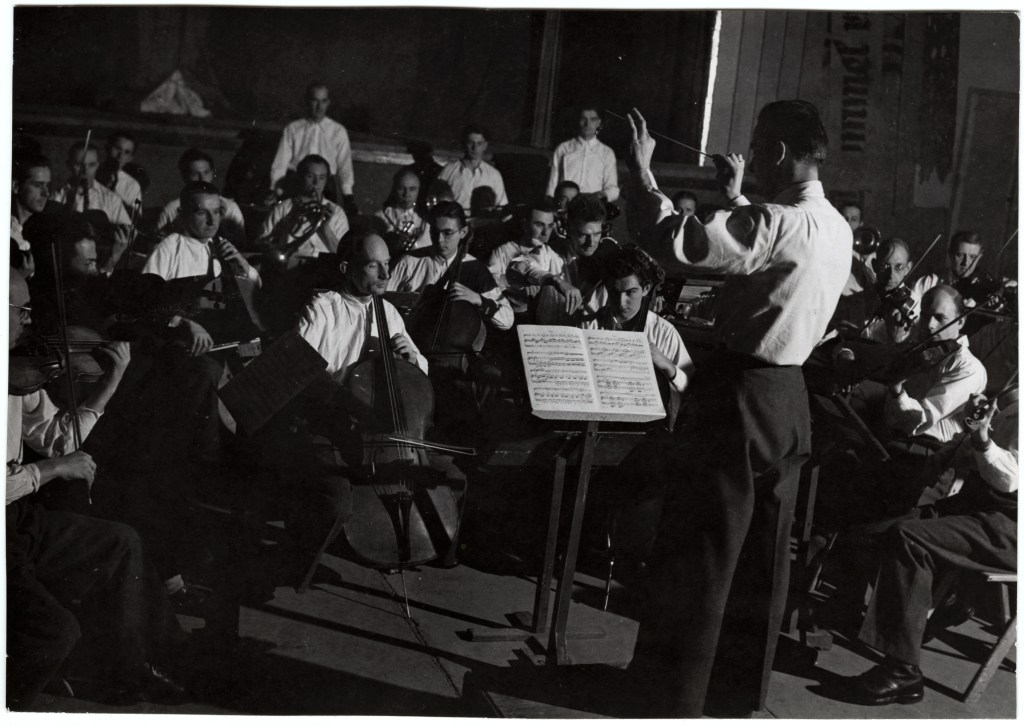

As of mid-1943, the camp had a thirty-two piece orchestra, an orchestra for “lighter classic music, various dance bands, a five-piece accordion band, and a choir. Concerts were often tributes to German musical history, although more popular pieces were played as well.

Sports were also especially popular activities thanks to the large open spaces within the enclosure. Football – or soccer – was the most popular sport and the many teams competed against one another within the camp so long as the weather cooperated. In the winter months, the prisoners flooded some of the soccer fields and turned them into ice rinks for skating and hockey. Equipment was provided by the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA.

As one of the largest internment camps in the country, Camp 132 was one of the largest suppliers of POW labour. Prisoners from Medicine Hat worked in bush camps throughout Northwestern Ontario as well as farms in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The camp also supplied POWs to the Riding Mountain Park Project (Whitewater Lake POW Camp) in Manitoba’s Riding Mountain National Park.

Prisoners were also employed in Medicine Hat, with groups working at the Medicine Hat Greenhouses, Medicine Hat Brick & Tile, and Medalta Potteries Ltd.

In 1944, prisoners at Camp 132 were granted permission to work on a farm not far from the camp. Known as the “Golden Valley Farm,” the POWs planted some 160 acres of potatoes, onions, cabbage, parsnips, beets, carrots, and turnips and produced more than 1,000 tons of vegetables in 1944. The farm not only kept POWs busy and provided them with a source of fresh vegetables, but surplus crops were sold and profits credited to their canteen fund.

Regardless of what was happening in camp – whether it be education, theatre, music, etc. – the internal administration strove to ensure that Nazi ideals and faith in the German war effort remained strong. An internal pro-Nazi and Gestapo-like administration monitored what was being said in programs and courses and took immediate action against those who doubted or spoke out against the Nazi cause. Their brutal methods became abundantly clear to Canadian authorities following the murder of fellow POWs August Plaszek and Karl Lehmann.

In July 1943, the pro-Nazi administration identified August Plaszek as a traitor due to his association with POWs who had served in the French Foreign Legion in the 1920s and early 1930s. On July 22, the camp administration called him and another POW for questioning but the pair made a break for the fence. While the one POW was able to seek the guards’ protection, Plaszek was seized by a mob and was later found dead in one of the recreation halls. Then, a year later, Karl Lehmann caught the attention of pro-Nazis in camp due to his anti-Nazi leanings. These Nazis then lured him into a classroom and murdered him on September 10, 1944 in order to send a message to anyone doubting the Nazi regime,

Canadian authorities were not oblivious to the power wielded by these Nazis. In order to break up Nazi control, leaders and members of this internal “Gestapo” were transferred to the newly re-opened Camp 100 at Neys. Although not a perfect solution, the transfer helped reduce pro-Nazi control at Medicine Hat.

As Canada began transferring POWs back to the United Kingdom for their eventual repatriation to Germany in early 1946, authorities made the decision to close Camp 132. The last group of POWs left Medicine Hat in April 1946 and the camp officially closed the following month.

In the nearly seventy years since the last prisoner walked out through the camp gates, all but two of the buildings have been removed. The camp area is now occupied by the Medicine Hat Exhibition Grounds, public parks, and housing developments. The two remaining buildings are the camp’s recreation halls and the West Recreation Hall is now owned by the Exhibition Grounds as serves as a storage space and exhibition hall while the East Recreation Hall has been re-purposed as the Patterson Armoury and has been home to local militia units since the early 1950s.

Location:

Pictures:

Further Reading:

- Posts about Camp 132 (Medicine Hat)

- Stotz, Robin Warren. “Camp 132: A German Prisoner of War Camp in a Canadian Prairie Community During World War Two.” MA Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1992.