Date Opened: November 1941

Date Closed: April 1945

Capacity: 650

Type of POW: Combatant Officers

Description:

With the arrival of several thousands POWs from the United Kingdom in 1940, Canada had to provide separate camps for combatant officers and other ranks. Under the terms of the 1929 Geneva Convention, officers and enlisted men were to be kept in separate internment camps. Officers, with the privilege of rank, were to be “treated with due regard to their rank and age” and, as such, generally enjoyed better living conditions than enlisted prisoners. While Canada initially interned German officers at Camp 20 (Gravenhurst), Camp 31 (Fort Henry), and Camp 100 (Neys), the latter two were deemed unsuitable for officers so work began on a new camp, Camp 30, near Bowmanville, Ontario.

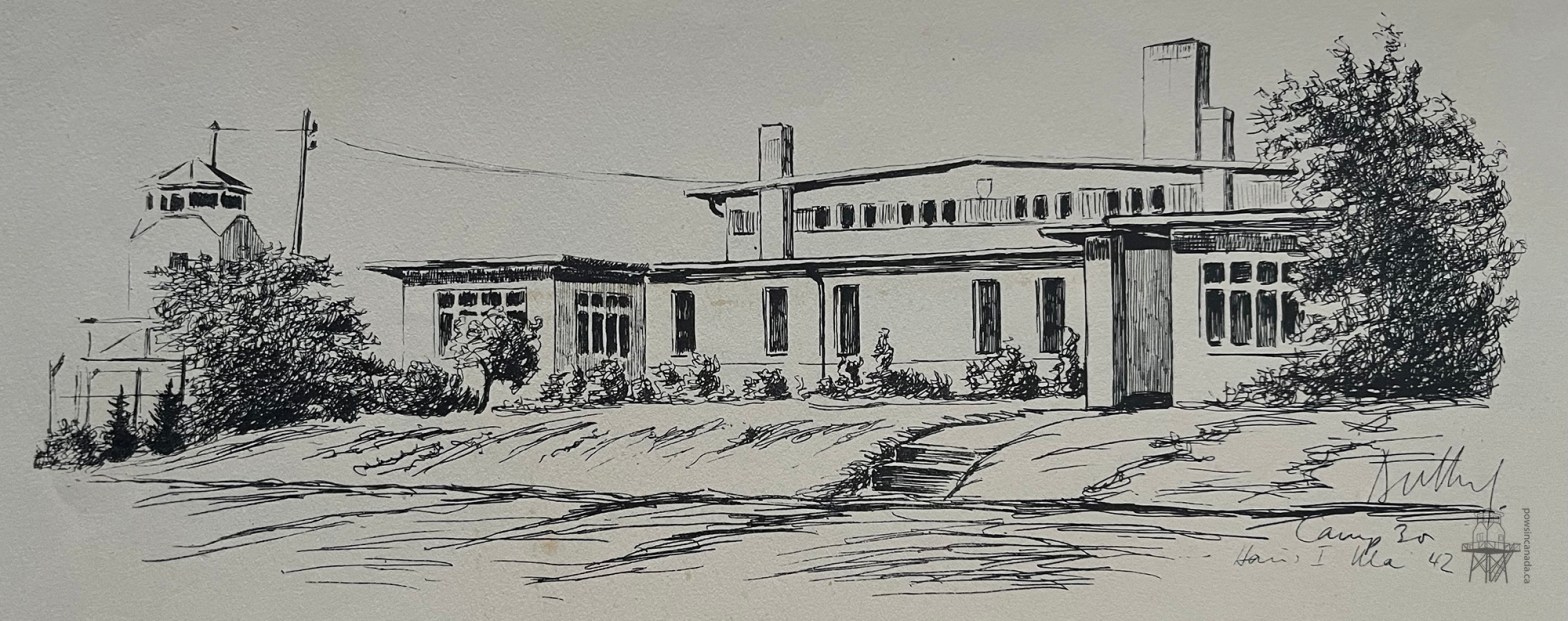

The Department of National Defence settled on using the Bowmanville Boys’ Training School on the east side Bowmanville for the new camp. With accommodation and messing to house over 600 officers already in place, the school made for an easy transition to an internment camp. Most of the school’s buildings were incorporated into the main enclosure, now surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers. A recreation building and an extension to the mess hall was added within the enclosure while quarters and messes for the guards and camp staff were erected on the east side of the camp.

The camp opened in November 1941 and the first prisoners, transferred from Camp 31 (Fort Henry), arrived on November 20. They were joined by more officers from Camp 100 (Neys) a few days later. They were a mix of Air Force, Navy, and Army officers, with a small number of other ranks to serve as orderlies, clerks, kitchen staff, and in other duties to assist with the day-to-day operation of the camp.

The officers soon settled into their new quarters and did what they could to busy themselves and help pass the time. In a letter to his sister, Bismarck survivor Hans Georg Stiegler described,

We make full use of the opportunity for sports. At present we are playing handball, football, hockey, fistball, basketball and tennis, however, with this limitation, that only one playing-field and a few tennis courts are available for 600 officers and 100 ratings. But with a good organization of course, everything is running smoothly. For entertainment every week two American talking-pictures are show; moreover, there are every month several performances by our theatre-group and our orchestras for concert-, dance, band, and string music. Already quite a number of good text books and fiction has been sent to us from Germany, and these are at the disposal of everyone, but are far from sufficient as to quantity. For a short time now it has been possible for our agriculturalists to busy themselves on a farm, so that almost everybody has the opportunity to keep himself busy. But this certainly is necessary as some of the officers were captured three years ago, whereas I have been shut up for only a year and a half. This waiting period is quite hard on us, but we shall stand it.

Translation of Letter from Ob. Faehnr. z. See Hans Georg Stiegler to Gertrud Ritsch, October 3, 1942. LAC.

Thanks to the site’s pre-war amenities, prisoners enjoyed access to a “first class” indoor swimming pool and gymnasium, the latter equipped with parallel and horizontal bars, vaulting horses, and weights. They also had a recreation field, boxing rink, five tennis courts, and a cinder running track. The tennis courts were flooded in the winter and transformed into skating and hockey rinks. As such, many prisoners spent much of their time outside, with soccer and tennis being the primary sports in the summer and hockey, gymnastics, and table tennis in the winter. Small groups were permitted parole walks outside the enclosure or bathing parties in a nearby creek.

Coursework occupied a significant portion of the prisoners’ time, with every prisoner in camp enrolled in at least one course during the 1943 winter and summer terms. Thanks to professional educators and the camp’s fifteen classrooms, prisoners were able to not only pursue courses on subjects of personal interest but prepare for university examinations or complete professional certifications in teaching, engineering, agriculture, trade, and the fine arts. Several guest lecturers from the University of Toronto also visited the camp and delivered talks on various subjects.

Any prisoner who so desired was provided with their own plot to grow flowers or vegetables and, with 18,000 flowers planted in 1943 alone, the camp was soon covered in well-kept lawns and flower beds. Prisoners initially access to a heated greenhouse to grow plants year-round but fuel shortages later prevented its use. Instead, groups of prisoners were permitted to work on a local farm that had been rented out. In 1944, prisoners planted potatoes, cabbage, oats, turnips, kohlrabi, beans, lettuce, Brussels sprouts, onions, spinach, cucumbers, corn, spices, cauliflower and tomatoes. They also raised and cared for roughly fifty pigs, several cows and calves, two horses, and over 350 chickens.

Professional and amateur musicians established a grand symphony orchestra as well as a brass band, dance band, and choir. A theatrical troupe performed shows like George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan” and Shakespeare’s “Comedy of Errors,” with the prisoners building and decorating their own sets and renting costumes from Toronto. A small group of puppeteers also entertained their comrades with puppet shows featuring hand-made puppets.

Like their comrades in Camp 20 (Gravenhurst), the prisoners also assembled their own makeshift zoo. In addition to wild animals captured in camp, the prisoners acquired – largely thanks to the help of the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA – several birds, raccoons, monkeys, turtles, fish, and, arguably the most unusual of them all, a small alligator.

Despite having arguably the best amenities of internment camps in Canada, several POWs remained adamant to remain active participants in the war and did their best to escape. Just days after the prisoners arrived, Ulrich Steinhilper squeezed through the wire fence and made his way to Niagara Falls before he was arrested. His attempt would be the first of many. Some made their way to the American border before they were re-captured, one POW attempted to steal a plane from the RCAF Station at Oshawa, and, in August 1943, guards discovered a 250′ tunnel that, while incomplete, extended 150′ beyond the enclosure.

The camp also made international headlines in October 1942 with what would become known as the “Battle of Bowmanville.” In response to Germany shackling Allied POWs in Europe, the British government requested Canada shackle POWs in response. The order was issued to several camps, including Camp 30. But when the Commandant informed the Camp Spokesman of the pending shackling, the prisoners proceeded to barricade themselves in several of the enclosure’s buildings.

After the prisoners refused to come out for roll call, the guards broke out into one of the barracks and the kitchen and seized several prisoners. The guards lacked the manpower to force the rest of the POWs out so the Commandant called for reinforcements from nearby training centres. The following day, over 400 Canadian soldiers entered the enclosure, half armed with clubs and the remainder with rifles and fixed bayonets, to force the prisoners out. The prisoners armed themselves with homemade clubs, hockey sticks, rocks, tins, dishware, and glass bottles, resulting in fierce close-quarter fighting as the Canadians forced themselves into the buildings. By the end of the day, the Canadians had succeeded and the prisoners were removed from their barracks. Some twenty Canadians and eighty POWs were injured in the process.

The prisoners at Camp 30 continued to test Canadian authorities for the rest of the war but, fortunately for camp staff, the “Battle of Bowmanville” was the be the worst. In December 1944, Camp 30 was designated a camp for “Grey” officers, a colour code that referred to those who were not staunch Nazis (categorized as “Black”) nor anti-Nazi (those deemed “White”).

The opening of Camp 135 (Wainwright) in 1945 made Camp 30 surplus to the Department of National Defence’s needs. The remaining prisoners were transferred to Camp 44 (Grande Ligne), Camp 130 (Seebe), and Camp 135 (Wainwright) over the coming months, with the final prisoners leaving Bowmanville on April 12, 1945.

The site was returned to the Ontario Government and it soon resumed its use as the Bowmanville Boys’ Training School. The school remained in operation until 1979, after which it was used for various academic purposes. The future of the site, in the hands of private developers, was up in the air until the former school and internment camp was declared a National Heritage Site in 2013. However, many of the buildings were vandalized in this time and those that remain are in various states of disrepair. Thanks to local interest, the Municipality of Clarington has taken over the site and hopes to turn it into a tourist attraction, preserving what is arguably the most intact site of a Canadian internment camp from the Second World War.

Location:

Pictures:

Further Reading:

- Posts about Camp 30 (Bowmanville)

- Hoffman, Daniel. Camp 30 “Ehrenwort”: A German Prisoner-of-War Camp in Bowmanville, 1941-1945. Bowmanville, ON: Bowmanville Museum, 1988.

- Camp 30 National Historic Site of Canada, Canada’s Historic Places