Date Opened: January 1941

Date Closed: July 1946

Capacity: 650

Type of POW:

– Combatant Other Ranks (January 1941 to June 1942)

– Japanese-Canadian Internees (June 1942 to July 1946)

Description:

Camp W (later Camp 101) at Angler, Ontario was one of Canada’s first two purpose-built internment camps of the Second World War and, more famously, was the location of the largest prisoner of war escape in Canadian history.

When the United Kingdom began transferring POWs to Canada in 1940, the Department of National Defence began expanding its network of internment camps. Camp R at Red Rock was the first camp to be opened in Northwestern Ontario but authorities had also identified two other locations well-suited for internment camps: one at the mouth of the Little Pic River and another at a highway construction camp used to build a nearby section of what was to become known as the Trans-Canada Highway. These two sites would later become Camp W (Neys) and Camp X (Angler).

Construction of the Neys and Angler camps began in Summer 1940. Military authorities originally intended to close Camp R (Red Rock) and transfer the internees to the two new camps but construction delays prompted the decision to use the new camps to house combatant prisoners. While Camp W at Neys was selected to intern officers, Camp X would hold other ranks, the first of whom arrived from the United Kingdom in January 1941.

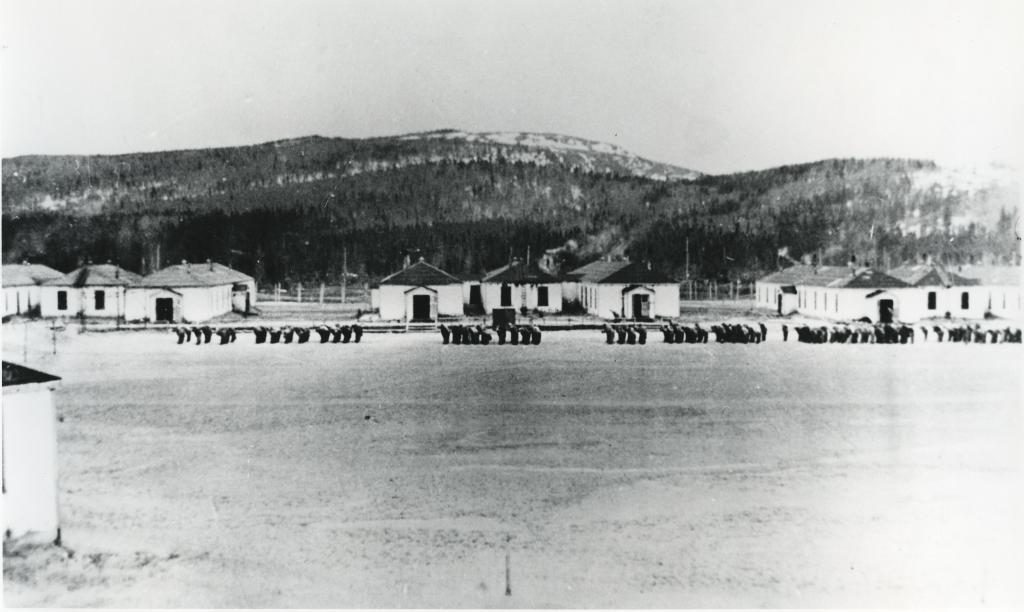

Like its sister camp at Neys, Angler had been selected for an internment camp largely due to its remote location and easy rail access. Two layers of barbed wire fencing – a total of 54km of wire – and a warning wire surrounded the unique, five-sided enclosure. Guards stood watch from five guard towers, each armed a Lewis machine gun (later replaced by Brens). Within the enclosure were four H-Huts housing the prisoners’ quarters, a 600-man kitchen and mess, a recreational hall, a tailor’s workshop, a detention hut, and a small hospital. Outside the enclosure were separate quarters and messes for officers and enlisted men, a recreation building, an administration building, a guardhouse, a supply depot, a garage, and a fifteen-bed hospital.

Arriving in the midst of a cold Canadian winter, the POWs quickly set about adapting to their new surroundings. With the help of the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA, the POWs improved their recreational spaces, building their own ping-pong tables as well as a platform and stage in the recreation hall. The organization also provided musical instruments, allowing the POWs to assemble a small orchestra, and a film projector, with which the POWs regularly showed films. Many prisoners busied themselves with educational courses of a variety of subjects including German, English, French, Spanish, literature, geography, mathematics, physics, geometry, and art.

As the snow melted, the prisoners were somewhat discouraged to discover the camp was built upon sandy soil that discouraged sports like football (soccer). But thanks to financial support from the War Prisoners’ Aid, the POWs set out to improve the grounds and succeeded in establishing a suitable recreation field. Once winter rolled around again, the POWs flooded part of the enclosure for a skating and hockey rink.

While most prisoners set to make the most of their internment, some were determined to remain active participants in the war. The result was that in April 1941 the camp witnessed the largest escape attempt in Canadian history. Shortly after midnight on April 19, 1941, a guard heard a noise behind his guard tower and a quick search revealed the opening of a tunnel some fifty feet from the tower. The alarm was raised and a count eventually revealed twenty-eight prisoners were missing. The guards immediately began searching the area while reinforcements from the Algonquin Regiment in Port Arthur and local RCMP and police dogs made their way to the camp.

Poor weather hampered search efforts but army and police patrols succeeded in recapturing nine of the twenty-eight prisoners by that afternoon, all of whom possessed detailed maps of Canada and the United States. A patrol found five prisoners sheltering in an abandoned shack in the early morning of April 20 but when the POWs were ordered to come out, they apparently attempted to flee. The patrol opened fire, killing two of the POWs and injuring another two. By April 21, nine prisoners were still missing, although three were found that day near Heron Bay. On April 24, police arrested two of the missing POWs, Karl Heinz Grund and Horst Liebeck, as they stepped off a train in Medicine Hat – over 1,700 km from the camp. Patrols picked up the last four POWs near Heron Bay on April 25, six days after their escape.

The two POWs killed in the escape, Herbert Löffelmeier and Alfred Miethling, were buried in a small cemetery just outside the camp. Walter Unk, who died spinal meningitis while at Angler, and Martin Müller, shot during an escape attempt from Camp W (Neys), would later be laid to rest in the same cemetery. The War Prisoners’ Aid provided the wood for the grave markers and the POWs carved the inscriptions.

In June 1942, the approximately 600 POWs at Angler were transferred to Camp 133 at Ozada, a temporary, tented internment camp intended to accommodate the arrival of thousands of POWs from North Africa until construction of Camp 132 (Medicine Hat) and Camp 133 (Lethbridge) was completed.

Camp 101 remained empty only briefly, for, shortly after the Germans’ departure, the Department of National Defence transferred almost 200 Japanese Canadian internees from British Columbia to Angler. These men included both Japanese Nationals and Canadian-born internees; among them was Hirokichi Isomura, a First World War Veteran who had fought for Canada in the 50th Battalion, and his son.

Like the POWs before them, the new internees quickly found ways to pass their time. Teachers and professors began offering courses in Japanese, English, German, geography, history, and writing. Although there were no professional musicians in camp, several internees put together a small orchestra with help from the War Prisoners’ Aid. Many internees busied themselves with sport, with wrestling, judo, jujitsu, tennis, baseball, and kendo in the summer and hockey and skating in the winter.

Over the following years, those willing to work were employed by the Pigeon Timber Co. and moved to company’s Neys-area bush camps. Others refused to work or accept conditional releases, instead preferring to wait until they could be reunited with their families in British Columbia.

By June 1946, there were 127 Japanese internees in Camp 101. Of them, seventy-four were Japanese Nationals, twenty-one were Naturalized Citizens, and thirty-three had been born in Canada. The vast majority had refused their release based on the conditions they had to work in Eastern Canada. They were transferred to Moose Jaw.

Camp 101 closed in July 1946. The camp was briefly taken over by the Department of Labour for housing Japanese-Canadians being relocated from British Columbia before the site was acquired by the Marathon Corporation in 1947. The buildings were subsequently dismantled and all salvageable materials relocated to the new community of Marathon. The Marathon Corporation then reforested the former camp site in 1960.

Location:

Pictures: