Date Opened: July 1940

Date Closed: January 1944

Capacity: 400

Type of POW: Italian Civilian Internees and Enemy Merchant Seamen

Description:

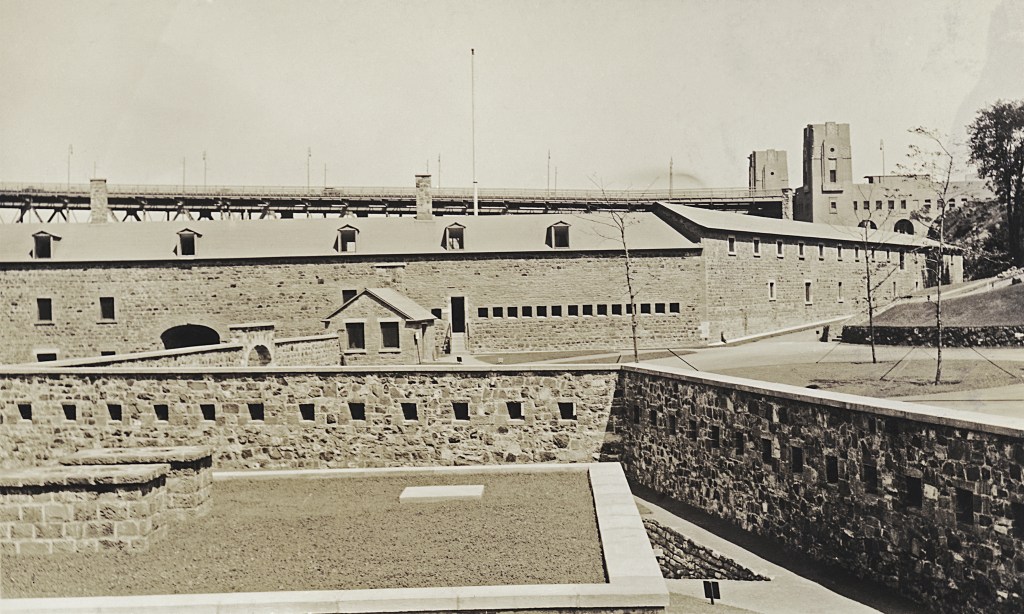

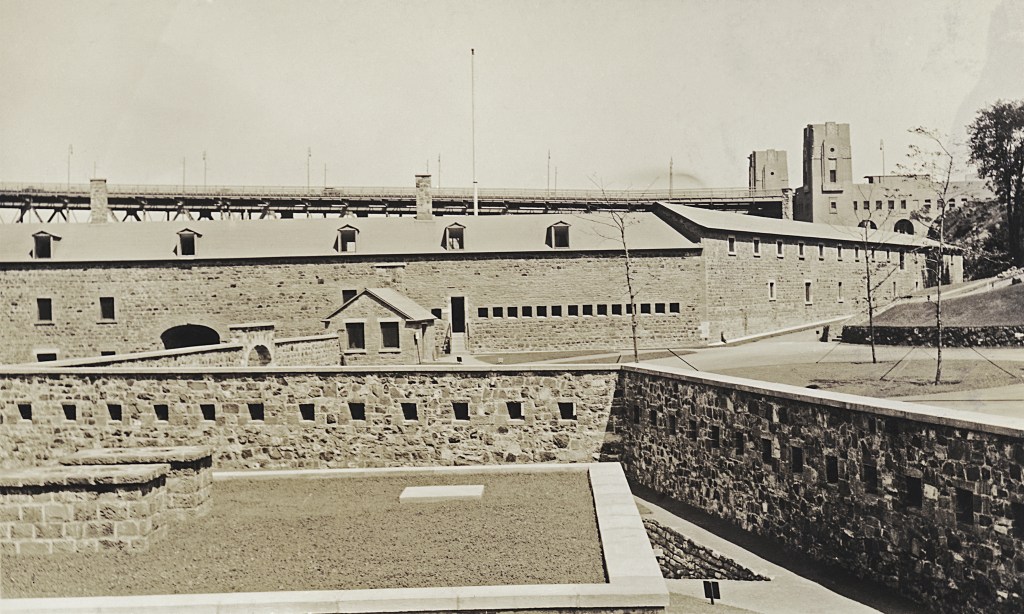

Canada’s decision to accept internees from the United Kingdom in mid-1940 prompted the opening of several new internment camps. Military authorities began selecting facilities that could be easily converted to camps in favour of building new ones. Historic military forts were relativley easy conversions and, as such, the Department of National Defence selected the Saint Helen’s Island Fort in Montreal for Camp S.

Along with Kingston’s Fort Henry and Île-aux-Noix’s Fort Lennoxe, the Saint Helen’s Island Fort was built in the 1820s as part of a defensive network of forts to protect Canada in the event of an American invasion. The island itself became a public park in 1874 and was a popular summer attraction for Montreal residents keen on swimming in the river or enjoying the beaches. The City of Montreal eventually acquired the fort and undertook extensive restorations in the 1930s.

Thanks to the renovations, the site required few upgrades to bring it up to the standards of an internment camp. After barbed wire fences were erected around an enclosure, Camp S opened in July 1940.

Four hundred and one Italian internees arrived from the United Kingdom on July 13. Considering Italy had only joined the war a month prior, many of the internees had been interned without an examination by a tribunal. Most expected to be released but, in the meantime, tried to make the most of their time behind barbed wire.

The prisoners and most of the guards were housed in the fort’s newly-restored buildings. The fort’s original three-story barracks housed the prisoners’ kitchen and mess, lavatory, and guard hospital on the ground floor; prisoners’ quarters, education room, detention cells, and hospital on the first floor; and the rest of the prisoners’ quarters, shoemaker’s shop, orderly room, and officers’ quarters on the second floor. Several new buildings were added, including a recreation hut and a sewing hut in the enclosure and additional guard quarters.

While the enclosure was surrounded by barbed wire fences, the camp had no guard towers. Instead, two machine gun posts and one sentry post overlooked the main enclosure while other sentry posts were established around the camp area.

Prisoners had access to a large study room on the main floor of their quarters but coursework does not appear to have been as popular as other camps. Only a quarter of the camp was engaged in coursework as of mid-1943, with internees studying Italian, German, French, Calculus, Italian Literature. The camp library had 1,000 volumes and was supplemented with the McGill University Traveling Library, which allowed for a constant circulation of books in camp.

Inside the enclosure, soccer remained the most popular sport but the prisoners also played tennis and bowled. A recreation hut situated within the enclosure offered a place for POWs to play table tennis, cards, chess, and checkers. The internees flooded part of their recreation grounds in the winter for use as a skating rink.

The POWs put together an eleven-piece orchestra as well as a classical trio (piano, violin, and clarinet), a classical duet (piano and violin) to entertain their comrades while a theatrical group, with several talented actors, put on regular performances. Handicraft was also a popular pastime, with some 100 internees engaged in woodcarving as of mid-1943.

The camp offered prisoners several opportunities to work through the POW Works Programme, which employed prisoners in voluntary, paid work. The work proved quite popular, employing 210 of the 288 internees in camp by mid-1943. Most were employed in the woodworking shop (located in the fort’s Powder House), building tables, forms, window frames, and packing cases, or in the sewing shop, producing articles like sheets, pillow slips, kit bags, and holdalls. Others worked on farms on the island while a select few worked in the guards’ messes as cooks, kitchen staff, and waiters, one of whom had worked as a waiter in London’s Savoy.

Several internees attempted to escape from Camp 43, although none were successful. Most took advantage of being outside the enclosure before making their getaway. In August 1941, for example, one internee succeeding in sneaking away from the woodworking shop and, after ditching his POW uniform in favour of civilian clothes hidden underneath, walked across the Jacques Cartier Bridge and made his way to Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu before he was apprehended. In July 1942, three other internees slipped way from a swimming party headed to the river and also crossed the bridge to Longueuil, where they took a bus to St. Luc, where they were eventually taken into custody.

The news of Italy’s surrender on September 3, 1943 brought was received with hope for the future – both for Italy and for an early release. The Commandant reported:

With the majority of the prisoners, it appeared to be very joyful news.

Lt.-Col. R.H. Duvar to Adjutant General, NDHQ, September 11, 1943, HQS 7236-94-6-43 – Intelligence Reports – Camp 43, C5416, RG24, LAC.

The terms of surrender did not seem to enter into the matter. There were so much jubilation that a half holiday was declared in the factory. Prisoners cutting a lawn inscribed a large ‘V’ in the grass, even the declared fascists appeared relieved although one declared Marshall Bedigilo had ‘let them down.’

The main concern of most, was for their families and friends in Italy.

While Italy’s surrender did not bring an immediate end to the internment of the Italian internees and EMS, their time at Camp 43 would soon be over. In order to reduce expenses of internment operations, the Department of National Defence elected to close the camp in late October. The remaining EMS and Civilian Internees were transferred to Camp 70 (Fredericton). Camp 43 remained on standby in the event it was needed again but it would never reopen.

After the war, the site was returned to the City of Montreal and restored to its prewar state. Montreal residents continued to make use of the island’s attractions and Saint Helen’s Island became a central location for Expo 67, requiring a significant expansion of the island. The old fort also housed the Stewart Museum from 1955 until its merger with the McCord Museum in 2021, resulting in the joint McCord-Stewart Museum.

Location:

Pictures:

Do you have a picture of this camp and are willing to share? Please get in touch.