This is the second post exploring the art of Otto Ellmaurer, a German-Canadian civilian interned in Canada during the Second World War. Missed the first part? Check it out by clicking here.

Continuing from last week’s, today’s post looks at more of Otto Ellmaurer’s cartoons, although these ones take a more joking look into internment at Kananaskis. Many of the cartoons appear to relate to specific events or inside jokes in the camps but, unfortunately, most of these stories have been lost.

Having already discussed parades, sick and injured prisoners would parade in front of the camp’s Medical Officer for evaluation and treatment. Here, the Medical Officer – likely Captain Robert Daniel Hewson – meets with sick and injured POWs and apparently he has had significant success; the chart in the background suggested there had been a rise in the number of medical cases (possibly as part of an organized resistance or protest) followed by a drastic decline – a secret cure perhaps?

Although not apparent in this print, a copy in the Canadian War Museum shows that the jug used to pour out the cure is “Castor Oil.” Know for its laxative effect, this likely explains the internee leaving the doctor’s office with his hand on his bottom and – if that was the medical officer’s cure-all – the significant decrease in the number of prisoners seeking out medical attention…

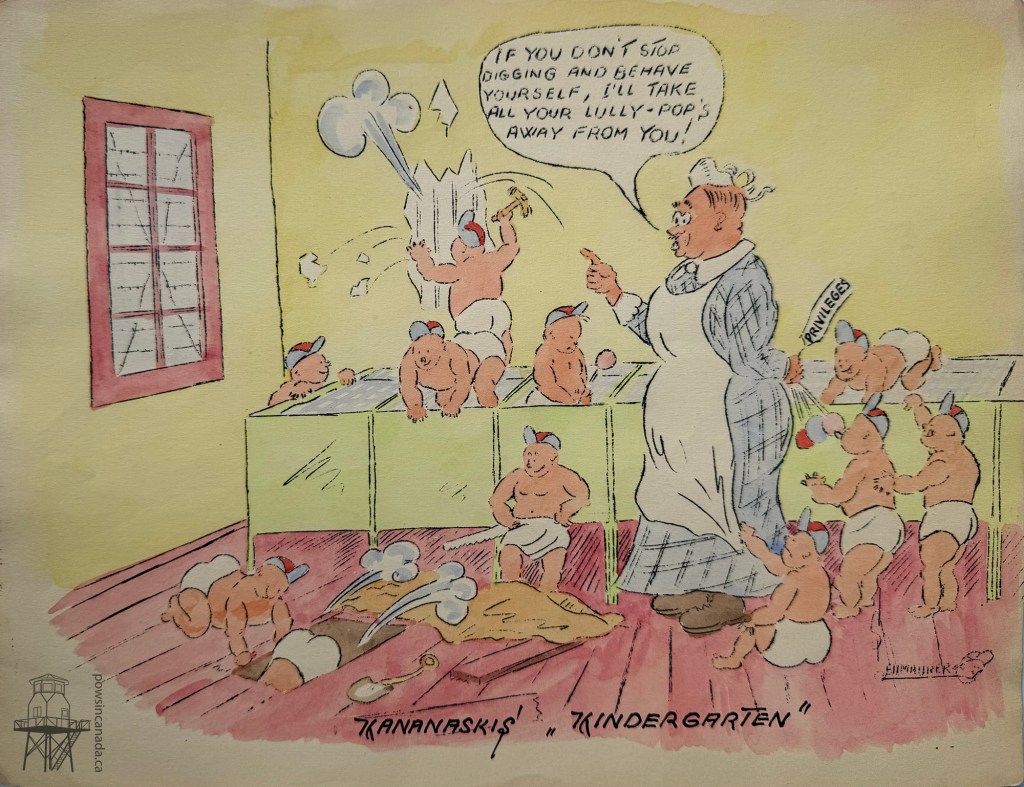

As the previous cartoon demonstrates, internees were often at the mercy of their captors, or at least their guards and the camp staff.

Here, Ellmaurer likens the relationship to internees as babies and the guards their nannies. Chaos appears to reign in the room, with some of the babies engaged in digging – and disappearing through – a tunnel under the floorboards, one destroys the barrack walls with a hammer, while several others are far more interested in the candies held behind the nanny’s back. Under the guards’ constant supervision and restricted in what they could do, the comparison between internees and children was apt. Threatening to remove internees’ privileges – lollipops in this case – was a very real tactic used in Canadian camps; threats to close camp canteens, remove newspapers and access to radios, cancelling recreational and work opportunities, confining POWs to quarters, or even eliminating deserts from the menus proved effective in avoiding or reducing trouble in camps.

While some of these threats seem trivial, these “privileges” were all important and valued to internees. Access to newspapers and radio, for example, provided prisoners with a connection to the outside world. Most camps had radios or speakers installed in recreation rooms where prisoners could listen to music or follow the latest war news but their use was often controlled lest the prisoners listen to unapproved stations or even attempt to make contact with the outside world.

Here, prisoners are returning their radio, claiming it simply wasn’t good enough. The 12 Tube shortwave radio they was out of the question. Not only would this have been a significantly more expensive model, but considering shortwave radios allowed listeners to tune into stations thousands of kilometers away rather than the limited range of higher frequency models. And there was always the concern that enterprising prisoners would use radio parts to build their own two-way radios.

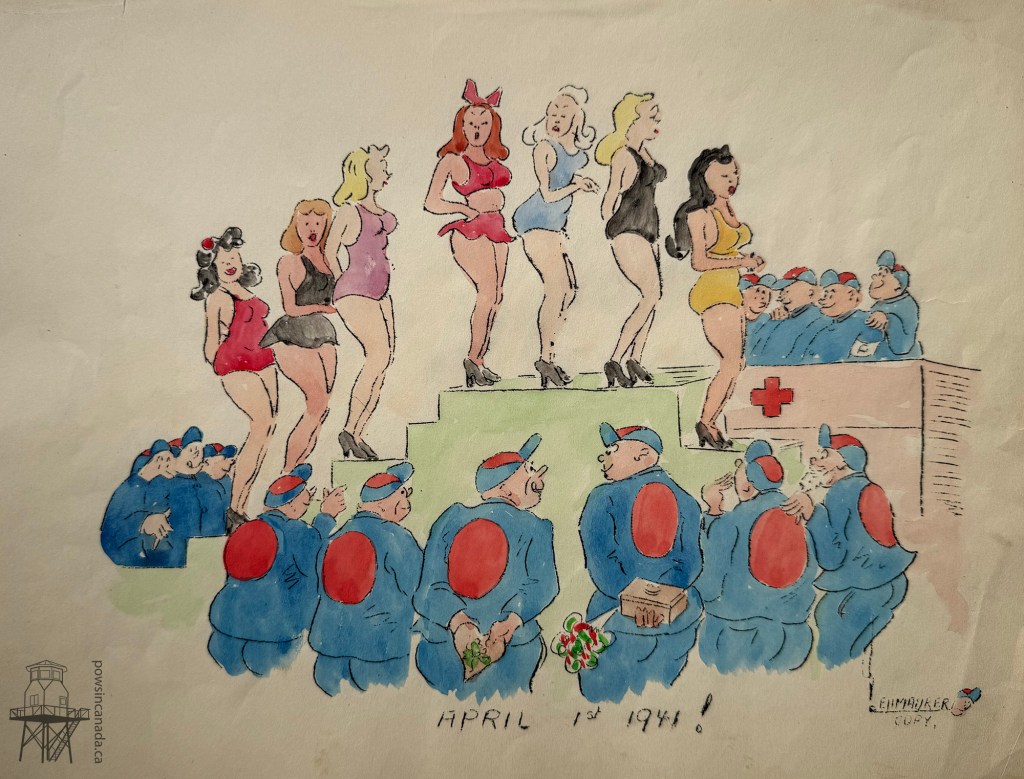

Of all of Ellmaurer’s cartoons, only one depicts women and this is not very surprising. Like the rest of Canada’s internment camps, the staff, guards, and internees in Camp K were men. Of the roughly 1,600 civilian internees arrested and detained in Canada, only twenty-one were women and they were interned in the Women’s Jail in Kingston, Ontario. As such, even sightings of women were rare occurrences in internment camps and internees’ only real contact with the opposite sex was through letters and postcards.

Ellmaurer’s “April 1, 1941!” print therefore raises a few questions. Were these women just a dream or fantasy? Was this a promise to the prisoners that turned out to be a joke? Or is he suggesting that these women are actually fellow internees in drag?

While women were often on the on internees’ minds, so was the thought of getting out of the camp. It is doubtful whether any prisoners, non-combatants and combatants alike, did not consider an escape, and those at Kananaskis were no exception.

Several internees did try escape from Camp K but none were successful. Here, two internees are caught by the guards after tunneling underneath the barbed wire fence. Their excuse? Searching for the Easter Bunny! While their search was evidently unsuccessful, the pair would have received a prize: a stay in the camp’s detention barracks.

While some escapees were caught in action, guards more often discovered tunnels during searches, with the help of informants, or simply by accident. This made identifying the culprits significantly more difficult and, in many cases, the potential escapees were never identified. But the next cartoon suggests a far more rare occurrence: internees confessing.

This unlikely trio stands in front of two officers (I believe the one rising from his seat is the Commandant, Lt.-Col. Hugh de Norban Watson) and a Sergeant and confessing to digging a tunnel. Whether or not these three actually dug the tunnel or are just taking the fall for their comrades is unknown as the officers are certainly surprised. Note the officer on the left eying up the prisoner’s ample waistline, presumably wondering how the three would fit through a small, cramped escape tunnel.

For the select few who did manage to escape beyond the camp bounds, they then had to make their way back to civilization. Camp K had been selected in part due to its isolation, with Calgary roughly seventy kilometers away, so prisoners had to choose their route wisely. Not to mention that, in the event of an escape, the guards set up checkpoints along all routes leading in and out of camp.

These internees apparently decided to hitchhike their way to Calgary after somehow leaving camp, but the ride they flagged down happened to be a truck full of guards. It is not clear who is more surprised, the truck driver or the prisoner! While several internees tried escaping from Camp K, some making their way as far as Calgary, they were all unsuccessful. The only guaranteed way out was a transfer to another camp or, in the best case scenario, their release.

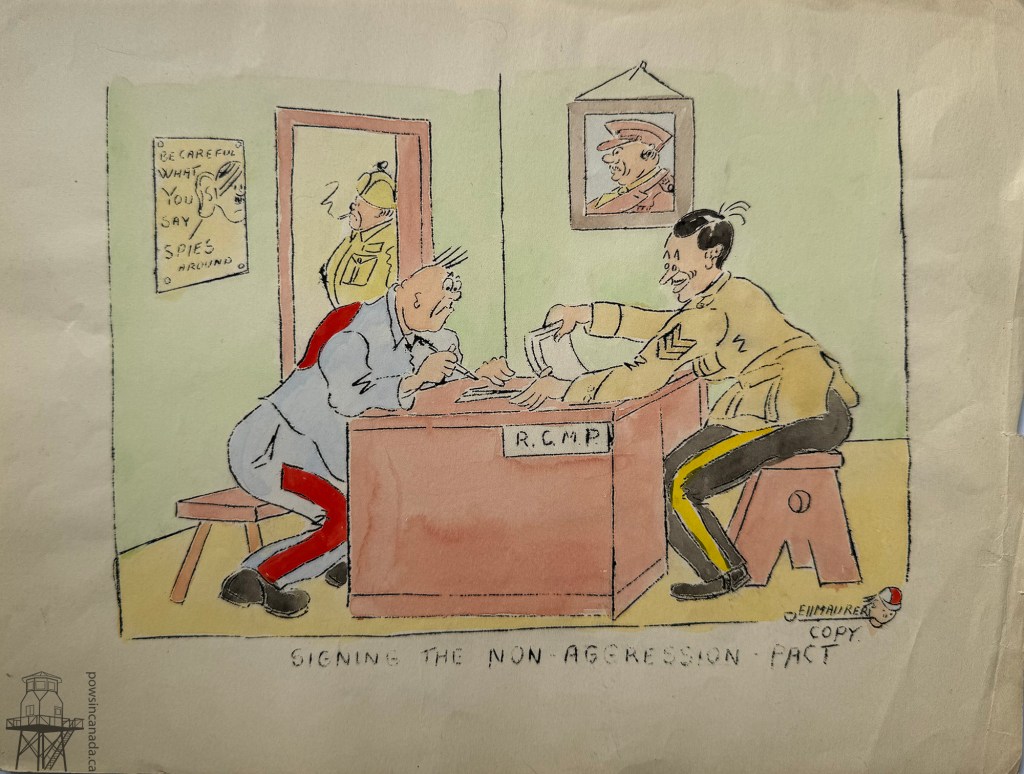

A play on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, this cartoon shows an internee signing a non-aggression pact for an RCMP Sergeant. The context of the “pact” is unclear but it could be referencing the terms of an internee’s parole release. As many of these internees posed no real threat, they were gradually released on a case-by-case basis. However, this did not make them “free” as the majority of these releases were conditional and any violation of these terms could mean re-internment.

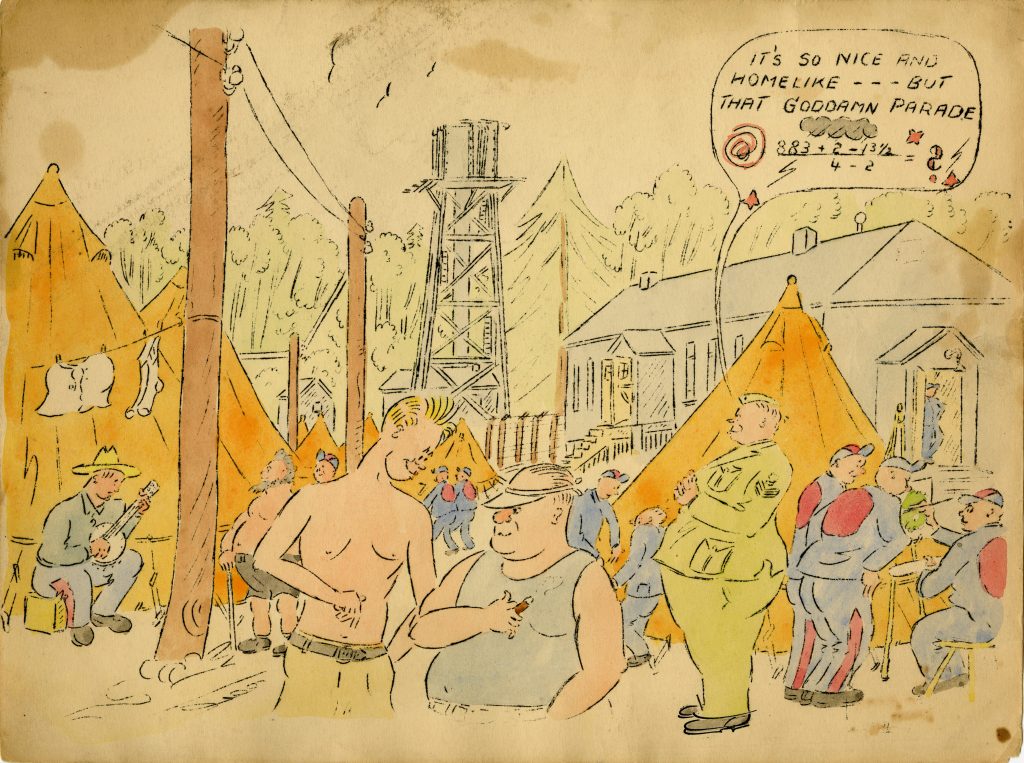

Ellmaurer was not among the lucky few to be released from Kananaskis. In July 1941, a year after arriving at Camp K, Otto Ellmaurer and the rest of the internees in camp were transferred to Camp B at Fredericton, New Brunswick as part of a reshuffling of Canadian internment operations. Departing camp by truck, the prisoners were taken to the nearest rail station and then spent the next few days traveling across the country by rail. Arriving at Camp B in early August, Ellmaurer continued to sketch and paint, although there appear to be fewer cartoons from this camp.

In one of the only known examples of his art from Camp B, a guard expresses his satisfaction with the camp being just like “home” – at least for a soldier, perhaps – but he is clearly dismayed with the prisoners’ lack of order during the daily parade. Notably, the internee wearing a visor and holding a cigar in the foreground is Camilliene Houde, a Quebec politician who was the Mayor of Montreal when he was interned in 1940 for protesting conscription.

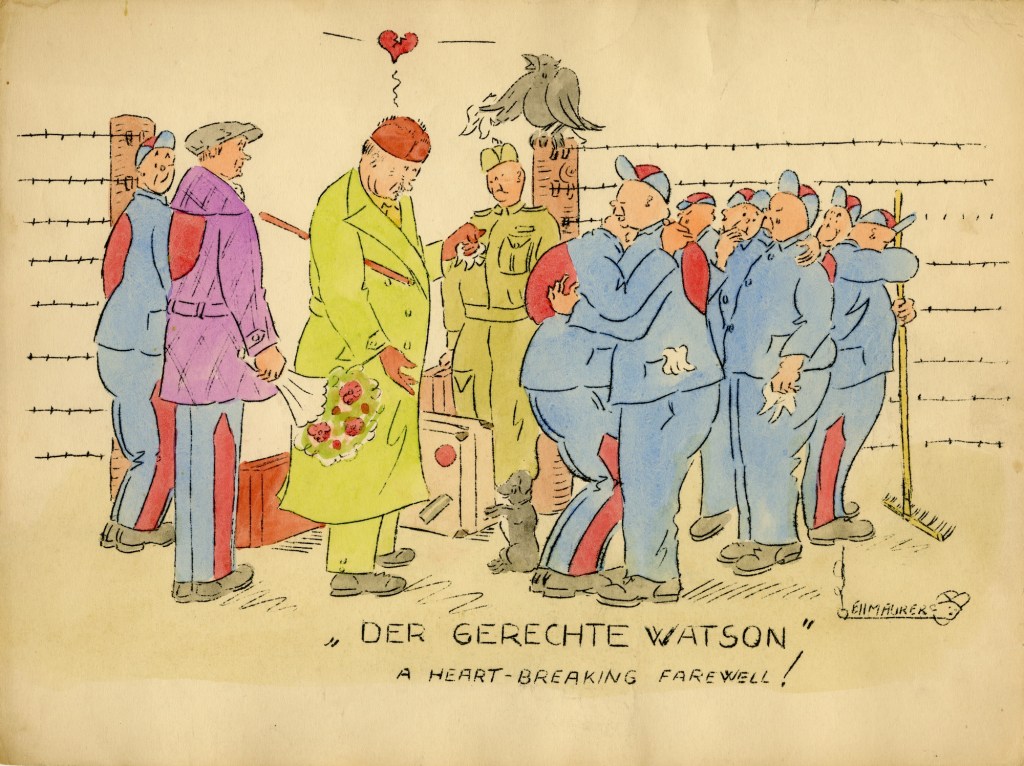

In February 1942, Lt.-Col. Hugh de Norban Watson, who had followed the POWs from Kananaskis to serve as the commandant of Camp 70, was transferred back to Camp 130. He was apparently respected by most of the internees and his departure was memorialized in an Ellmaurer print.

Here the prisoners and Watson say their goodbyes. Camp Spokesman Johannes Brendel once again appears in his purple jacket, this time holding flowers; Watson appears to be heartbroken, gesturing or perhaps tossing a red ball to a small dog; while the remaining prisoners – and the crow – console themselves.

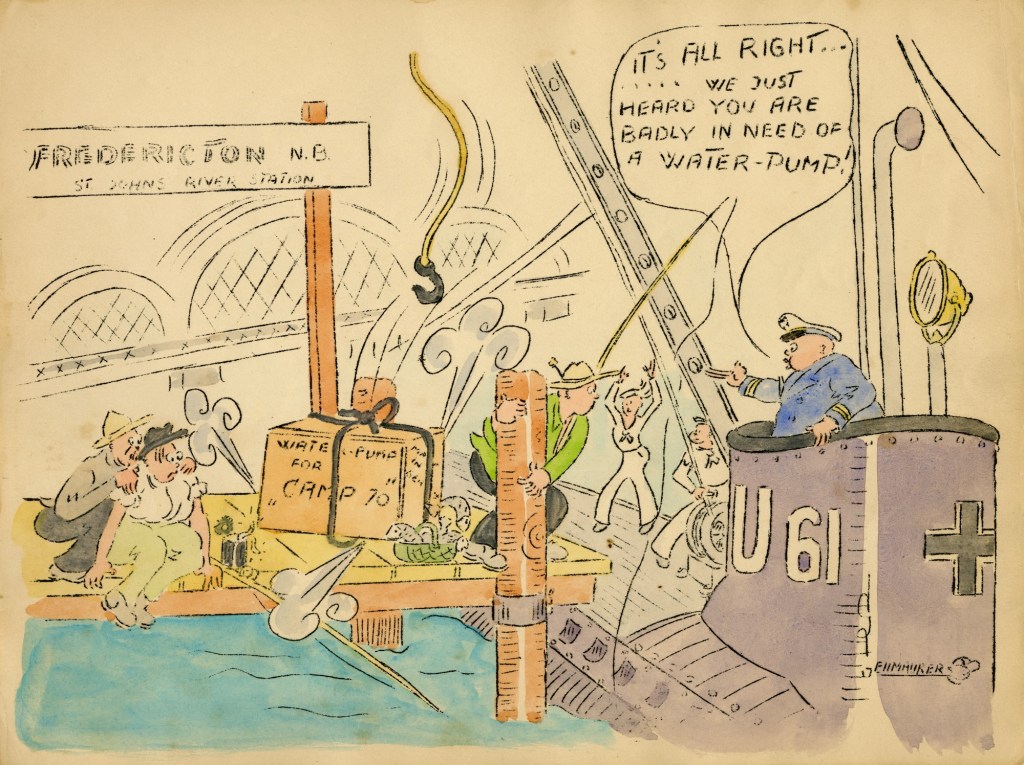

In 1942, the camp struggled with an inadequate water supply and the need for a new pump proved a contentious issue in camp. Difficulties in obtaining said pump from the United States meant the prisoners were still waiting in July 1942 so, rather than wait for the Canadians to source the pump, Ellmaurer depicted an alternative solution:

The cartoon shows German Submarine U-61 docking in Fredericton along the St. Johns River and dropping off the much-needed water pump to the surprise of the locals. While the camp did finally receive the pump in the latter half of 1942, it was sourced through official channels rather than the Germany Navy.

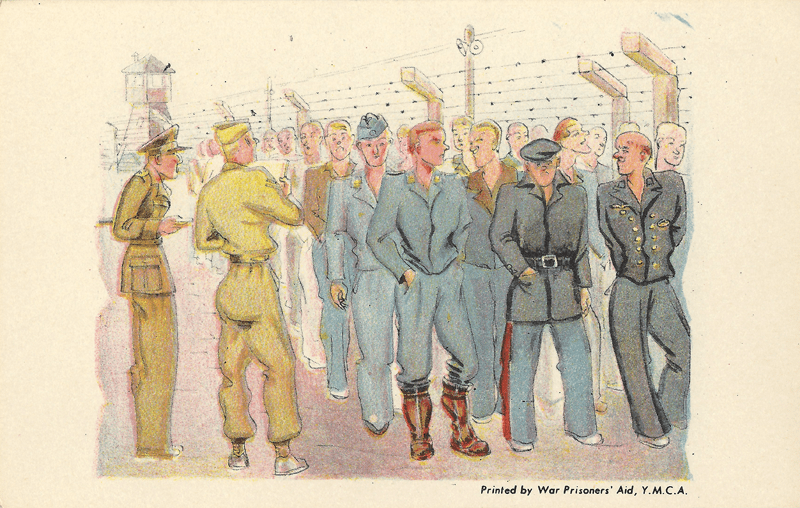

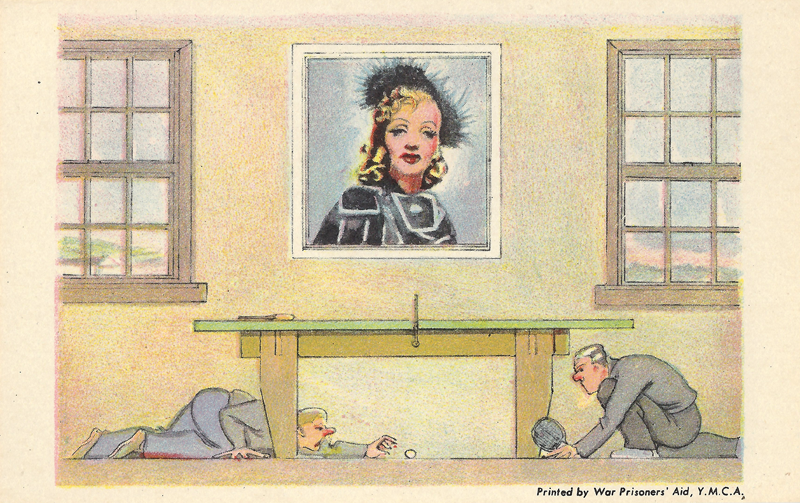

While I am not aware of other cartoons in this series, Ellmaurer did continue sketching and painting at Camp 70. Among his works was a series that, along with some art from fellow POW artist Joachim von Quillfeldt, was selected by the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA for use as souvenir postcards for prisoners of war interned throughout Canada.

Although these were done in a different style than his Kananaskis cartoons, this series also took a more light-hearted view of internment. A total of nineteen cards – fifteen I believe by Ellmaurer and four by von Quillfeldt – were selected and thousands of copies were printed and distributed to internment camps across Canada. Prisoners were permitted to purchase these cards from the camp canteens and while some chose to mail them back home as postcards, most kept them as souvenirs. Check out the link below to learn more about these cards.

Otto Ellmaurer was eventually released from Camp 70 in October 1944. He returned to the Quebec, moving to a farm owned by his brother, Anton, who had managed to avoid internment. In 1950, he left the farm and returned to Montreal and, shortly after, was joined by his son, Otto W. Ellmaurer, who had stayed in Germany to complete his education. Following in his father’s footsteps, Otto Jr. also became a draughtsman and established himself as a talented artist in the Dorval region. Otto Sr. appears to have remained in Montreal until his passing in 1979. He is buried in Montreal’s Cimetière Mont-Royal.

While Otto Ellmaurer may not have received fame and recognition for his art, many internees kept his prints as cherished souvenirs and reminders of their internment and thousands more kept his postcards. While life in an internment camp was rarely as light-hearted as the prints suggest, Ellmaurer’s art no doubt brought a smile and laugh to many an internee.

If anyone has other examples of Otto Ellmaurer’s art or knows more about the stories depicted in these cartoons, please leave a comment below or get in touch.