Some eighty-four years ago, on May 27, 1941, British battleships and torpedo bombers engaged the Bismarck – Germany’s famed battleship – in its final battle. The ship sustained heavy casualties and crippling damage before the surviving crew scuttled the ship to avoid it falling in British hands. The survivors abandoned ship and the Bismarck soon slipped beneath the waves. Of the 2,200-man crew, 110 were rescued by British vessels and another five by German vessels. The survivors picked up by the British were now prisoners of war. But these men would not end up waiting out the war in a British internment camp; instead, they soon found themselves prisoners of war in Canada.

Although the ship had a relatively short career, the Bismarck has continued to captivate interest some eight decades after its sinking. Laid down in July 1936 and commissioned in August 1940, the Bismarck was one of the largest battleships of the Second World War, with a crew of over 100 officers and almost 2,000 enlisted men. The ship’s eight 38cm guns, twelve 15cm guns, and numerous anti-aircraft guns and thick armour made it a formidable opponent.

In May 1941, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen engaged the British HMS Hood and HMS Prince of Wales in the Battle of the Denmark Strait, which culminated in the Hood‘s sinking. The Bismarck suffered heavy damage in the battle and the ship was forced to make its way back to France for repairs. But before the Bismarck could reach safe waters, British torpedo bombers, battleships, and heavy cruisers attacked the ship and caused catastrophic damage. The Bismarck’s surviving crew members had no choice but to abandon ship and the vessel disappeared in the cold North Atlantic waters.

The British heavy cruiser Dorsetshire picked up eighty-five survivors and the Maori another twenty-five before a lookout spotted what he believed to be a German U-Boat periscope and sounded the alarm. The remaining survivors were abandoned although a German U-Boat rescued three more men and a German weather ship picked up another two the following day. The 109 survivors in British custody (one survivor succumbed to his wounds) were now prisoners of war and transferred to the United Kingdom.

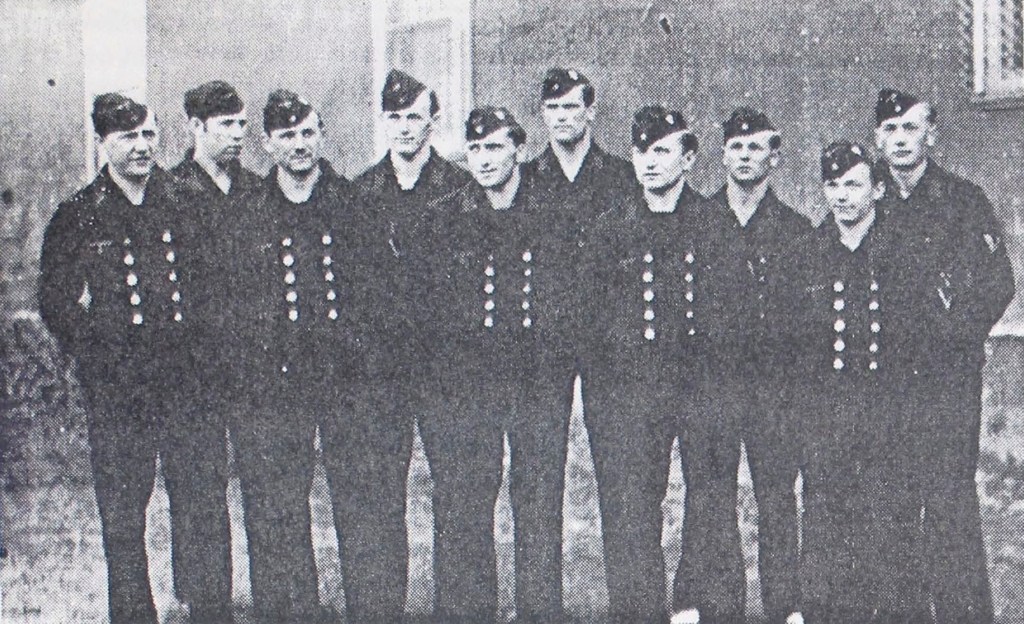

Shortly after their arrival on British soil, some seventy-five prisoners were interrogated to learn about the ship and German Naval activity. Inexperience and their young age – many were under the age of twenty – meant British authorities obtained little useful information. The prisoners were then transferred to various internment camps across the United Kingdom but their time in the country was short-lived. In late 1941, the enlisted crewmen of the Bismarck were among 1,000 German POWs transferred to Canada. The prisoners arrived in Halifax in January 1942 and were quickly offloaded onto trains to take them to their next “home.” For the crew of the Bismarck, this was Camp 23 at Monteith, Ontario.

Originally a provincial detention facility, Camp 23 was first repurposed to hold civilian internees in 1940 but was later expanded to hold combatant prisoners in 1941. The camp would eventually reach a capacity of 4,000 prisoners, dwarfing the village of Monteith and claiming the title of Ontario’s largest internment camp of the Second World War.

To help pass the time, Canadian authorities encouraged a variety of recreational activities in camp and many prisoners busied themselves with activities like sports, music, theatre, educational courses, art, and handicrafts.

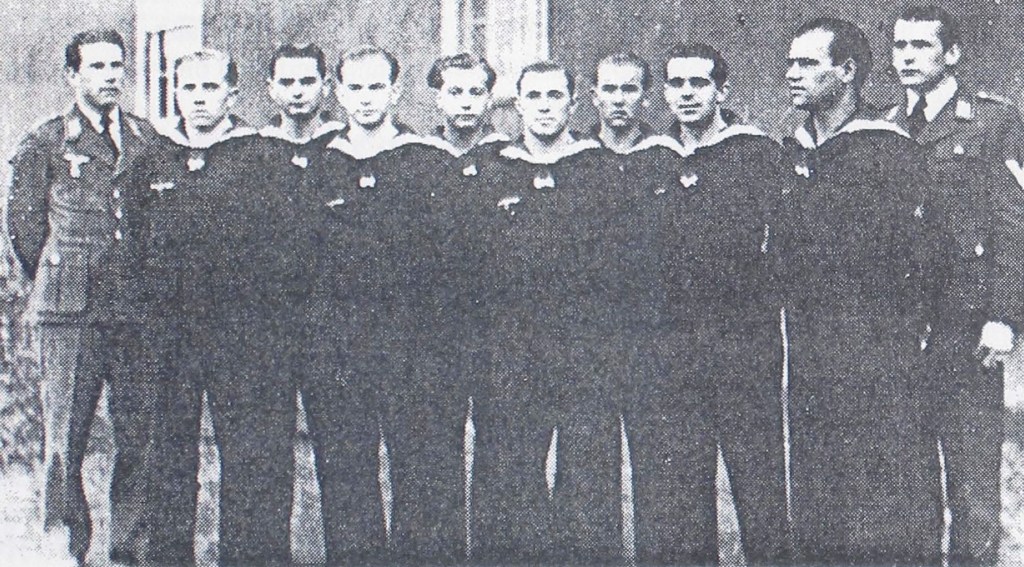

While the enlisted men settled into their new quarters in Northern Ontario, the surviving officers – Leutnant Lothar Balzer (Meteorologist), Kapitänleutnant Burkard Freil Müllenheim-Rechberg (Artillery Officer), Kapitänleutnant (Ing.) Gerhard Junack, and Fähnrich Hans-Georg Stiegler – remained in the United Kingdom for a few more months before they too were transferred to Canada. Arriving at Halifax in April 1942, the four were transferred to Camp 30, a German officers’ camp, at Bowmanville, Ontario.

The prisoners at Camp 30, thanks to their rank, generally enjoyed better living conditions than their enlisted counterparts at Monteith. As a former boys’ school, Camp 30 included a swimming pool and gymnasium, a recreation field, and tennis courts, not to mention classrooms, dormitories, and a large dining hall. Some six months after arriving, Hans-Georg Stiegler described life in Bowmanville in a letter to his sister:

We make full use of the opportunity for sports. At present we are playing handball, football, hockey, fistball, basketball and tennis, however, with this limitation, that only one playing-field and a few tennis courts are available for 600 officers and 100 ratings. But with a good organization of course, everything is running smoothly. For entertainment every week two American talking-pictures are show; moreover, there are every month several performances by our theatre-group and our orchestras for concert-, dance, band, and string music. Already quite a number of good text books and fiction has been sent to us from Germany, and these are at the disposal of everyone, but are far from sufficient as to quantity. For a short time now it has been possible for our agriculturalists to busy themselves on a farm, so that almost everybody has the opportunity to keep himself busy. But this certainly is necessary as some of the officers were captured three years ago, whereas I have been shut up for only a year and a half. This waiting period is quite hard on us, but we shall stand it.

Translation of Letter from Ob. Faehnr. z. See Hans Georg Stiegler to Gertrud Ritsch, October 3, 1942. LAC.

The Bismarck’s fame was widespread even in Canada and the ship became a popular subject for POW craftsmen who began producing models of the famed ship. Some of these craftsmen are believed to be Bismarck survivors but the ship’s popularity attracted the attention of many others talented model makers. Countless wooden models, such as the one below attributed to Bismarck crewman Erwin Blödern, were produced by prisoners in camps across the country and gifted or traded to their comrades or, in the latter years of the war internment, sold in organized sales to camp staff, guards, and select members of the public.

As the months passed, some of the Bismarck crewmen were transferred to other internment camps as Canadian authorities opened new camps and shuffled prisoners around. Several of the enlisted men were transferred from Camp 23 to Camp 132 at Medicine Hat, Alberta after the camp opened in 1943, while others soon found themselves working in prisoner of war labour projects.

Following the Canadian government’s approval of prisoner of war labour in May 1943, many of the Bismarck‘s former crew were transferred to remote bush camps across Northwestern Ontario. Prisoners like Fritz Dernbauer, Ernst Kadow, Heinz Meurer, Willi Treinies, Heinz Jucknat, and Helmut Keune volunteered or were selected for work in these small, isolated camps where they cut, stacked, and hauled pulpwood in exchange for 50¢ a day and the opportunity to live and work in relative freedom. With no barbed wire fences or guard towers surrounding these camps, many prisoners spent their free time exploring, hiking, swimming, canoeing, and skiing.

Germany’s surrender in May 1945 brought hopes of soon returning home to Germany but Canada did not begin transferring prisoners to the United Kingdom until 1946. Those prisoners working in bush camps would remain there until the Spring or early Summer at which point they too were transferred back to the base camps for their eventual repatriation. Some volunteered to remain in Canada and work on farms for the rest of the Summer, motivated by the hope of avoiding repatriation and starting a new life in Canada. Their plans, however, were dashed when the Canadian government elected to transfer all its prisoners to British custody by the end of 1946. There was, however, one exception from the Bismarck crew: Helmut Keune.

After spending almost two years in Camp 23 (Monteith), Keune had volunteered for outside work and began working for the Nipigon Lake Timber Company at one of the company’s bush camps near Longlac, Ontario. In March 1946, Keune fractured his spine in a work accident, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. He spent five years recovering in a Toronto hospital before he was finally released in 1951 and, in an exceptionally rare occurrence, was granted permission to remain in Canada. You can read more about his story at the link below.

As for the rest of the Bismarck crew, they would spend the rest of 1946 working on farms or on other projects in the United Kingdom before they were finally repatriated to Germany in 1947. Most picked up the lives they had left behind almost seven years prior, but some never gave up their hope of returning to Canada. In the 1950s, several prisoners emigrated to Canada or the United States to start a new life in the post-war era. Heinz Jucknat, for example, spent part of the war working in a bush camp near Kapuskasing, Ontario and liked it so much that he chose to return there in the 1950s. He raised his family in Kapuskasing and lived there until his passing in 1998.

The last known Bismarck survivor, Bernhard Heuer, passed away in 2018.

Canada is rarely mentioned in stories of the Bismarck despite the crew being sent here to wait out the war. Nearly all of the survivors spent twice as much time as prisoners of war in Canada than did they did aboard the famed battleship. Despite the significance of their POW experiences, prisoners’ stories have all too often been overshadowed by their combat careers.

Bismarck Survivors Sent to Canada1

- Lothar Balzer

- Helmut Behnke

- Wilhelm Beier

- Walter Bieder

- Erwin Blödorn

- Herbert Blum

- Hans-Joachim Bornhuse

- Hermann Budich

- Erich Burmester

- Franz Chyla

- Friedrich Dernbauer

- Johannes Dörfler

- Willi Draheim

- Adolf Eich

- Willi Fahrenbach

- Anton Geierhofer

- Wilhelm Generotzky

- Wilhelm Gräf

- Paul Gran

- Alois Haberditz

- Werner Hager

- Franz Halke

- Heinz Heinecke

- Johann Hellwig

- Friedrich Helms

- Ernst Hepner

- Bernhard Heuer

- Paul Hillen

- Fritz Hoeft

- Herbert Janh

- Günther Janzen

- Heinz Jucknat

- Gerhard Junack

- Friedrich Junghans

- Johann Juricek

- Ernst Kadow

- Wilhelm Kaselitz

- Willi Keller

- Helmut Keune

- Theodor Klaes

- Gerhard Klotzsche

- Otto Kniep

- Heinrich König

- Karl Kuhn

- Willi Kühn

- Heinrich Kuhnt

- Adolf Kunkel

- Walter Kunze

- Herbert Langer

- Kurt Langerwisch

- Rudolf Lerch

- Kurt Liebs

- Werner Lust

- Josef Mahlberg

- Rudolf Martin

- Fritz Mathes

- Fritz May

- Heinz Meurer

- Wilhelm Mielke

- Walter Mihsler

- Heinrich Mittendorf

- Burkard Freiherr von Müllenheim-Rechberg

- Peter Müller

- Wilhelm Ottlik

- Otto Peters

- Herbert Prinke

- Gerhard Raatz

- Ernst Rademann

- Erich Reubold

- Johann Riedl

- Ernst Risse

- Bruno Robakowski

- Wilhelm Rohland

- Rudolf Römer

- Paul Rudeck

- Günther Rühlke

- Bruno Rzonca

- Walter Sander

- Ernst Schäfer

- Gerhard Schäpe

- Alfred Scheidereiter

- Max Schittke

- Karl Schmidt

- Wilhelm Schmidt

- Eduard Schmitt

- Wilhelm Scholz

- Karl Schreimaier

- Karl-August Schuldt

- Heinz Seelig

- Herbert Seiffert

- Rudi Siebert

- Hans Sobottka

- Hans Springborn

- Heinz Staat

- Josef Statz

- Heinz Steeg

- Hans-Georg Stiegler

- Richard Teetz

- Willi Treinies

- Kurt Trenkmann

- Hans Wachholz

- Helmut Walter

- Herbert Walter

- Walter Weintz

- Hermann Weymann

- Rudolf Wiesemann

- Erich Wollbrecht

- Heinrich Wurst

- Bruno Zickelbein

- Johannes Zimmermann

- Adapted from bismarck-class.dk (archived) and kbismarck.com. ↩︎

As you know, meaningful friendships, camaraderie, are formed in battle situations. My father-in-law Charles James Pickersgill served in the British Navy. He served on the H.M.S. Hood. He was suddenly transferred to a different vessel. The next time the Hood went out, the battle with the Bismarck took place and the Hood perished. C.J. never fully recovered from the loss of all his good friends, his comrades. It was a terror that lived within him. The net of victims has a wide capture.