By Spring 1945, Allied advances in Europe suggested that it was only a matter of time before Germany surrendered. But for the guards stationed at Camp 100 at Neys, Ontario, their work was far from over. Camp 100, since its re-opening in September 1944, had been designated to hold ardent pro-Nazi troublemakers transferred from Camp 132 (Medicine Hat) and Camp 133 (Lethbridge). Despite the war nearing its end, many of the POWs remained firm in their belief that Germany would somehow emerge triumphant and, as such, continued to resist against their internment and their guards. Authorities were unsure how prisoners would react to the news of Germany’s surrender but a discovery of a homemade weapon raised significant concerns about how far pro-Nazis might be willing to go.

After its establishment in May 1940, the Veterans Guard of Canada took responsibility for guarding and administering Canada’s internment camps. Each camp was guarded by a guard company that rotated through different internment camps every month but the camps were administered by a permanent staff. This included the Commandant, Adjutant, Quartermaster, Medical Officer, Cooks, Clerks, and the Scout Section.

The Scouts were a small but essential group whose primary responsibility was to prevent prisoners from escaping. While guards manned guard towers and patrolled outside the barbed wire fences, the hand-picked scouts patrolled within the enclosure. Scouts were the first line of defence and, as one officer described, served as the Commandant’s “eyes and ears – even his nose and the tips of his fingers.” Unarmed, these men kept watch on the POWs searching for any signs or irregularities that could suggest the prisoners were planning escape or other trouble.

Although they all worked in the enclosure, Scouts were divided between different tasks, earning nicknames associated with their duties. The aptly named “Gophers” searched and probed the ground for tunnels in the enclosure while “Ferrets” focused their attention under roofs and floors for any sign of escape. Several escape attempts were foiled by the keen eyes and ears of camp scouts but these men also helped in the discovery and seizure of illicit items in camp. Scouts uncovered an array of material ranging from civilian clothing and currency to hidden radios and escape supplies. But in late March 1945, one of the “Gophers” made a discover that emphasized the risk of guarding potentially fanatic enemy combatants.

In March 1945, one of the Camp 100 Scouts, Private F.W. Cooper was assigned a special task: secretly observe POWs in one of the barracks for subversive activity. From his hiding spot, Cooper kept watch on the prisoners and, much to his surprise, he discovered they were building something that resembled a weapon. He reported the matter to his superiors who then informed Camp Commandant Lt-Col. S.C. Sweeney. Sweeney elected to allow the POWs to finish the weapon – under the careful watch of the scouts – before taking action. Cooper resumed his watch as the POWs continued their work over the following days. Then, on April 19, he watched through a hole in the ceiling as the POWs successfully tested the weapon. Cooper reported the test to his superior, Scout Sergeant Harry Kline, who informed Lt-Col. Sweeney. Sweeney, escorted by several scouts, proceeded into the enclosure under a guise of a morning inspection. Upon entering the building, the scouts revealed the hiding place and pulled a homemade crossbow from its hiding spot.

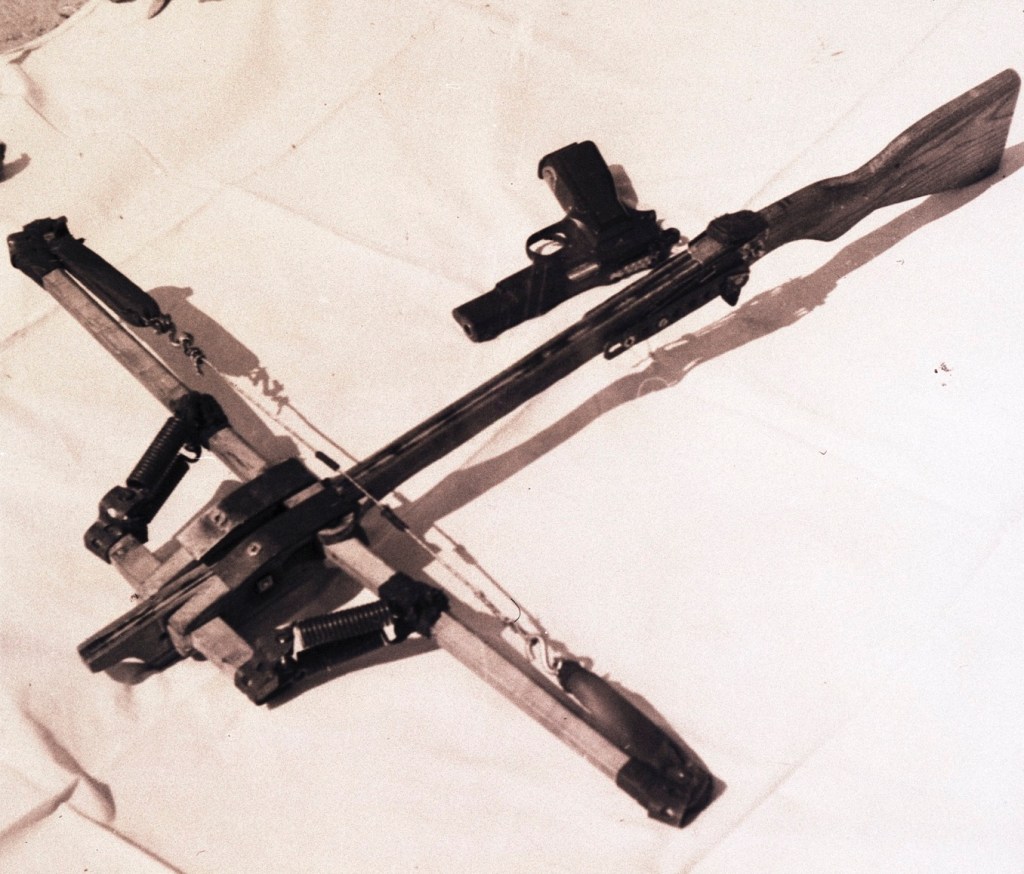

Coined “The Silent Killer” by the guards, the crossbow weighed four pounds, measured approximately 30” long, and had a 24” bow. An examination from the camp armour revealed that the bow was built entirely from material salvaged within the camp; the springs came from bed springs, the bow string from woven cable, the rubber from an inner tube, the trigger spring from a knife blade, and the wood stock was carved from a folding bench.

Although no bolts could be found, the armourer produced an improvised bolt and tested the crossbow. The results demonstrated that a steel rod could penetrate an inch into softwood at 25 yards. In other words, it could kill.

The purpose of the crossbow remained unknown and the POWs refused to divulge any further information. The Commandant gave three likely options:

- to kill an Anti-Nazi POW in camp

- to kill a member of the camp staff

- to kill game for food after escaping from camp

The crossbow’s discovery prompted the Directorate of Internment Operations to issue a warning to all internment camps to show what inventive POWs were capable with materials commonly found around camp.

It is unknown what punishment the prisoners responsible received. Following an investigation, they would have likely received up to a twenty-eight sentence in the camp’s Detention Barracks.

As for the crossbow, it was forwarded to military authorities in Ottawa for further evaluation and, in the following years, fortunately made its way into Canadian War Museum‘s collection, where it resides today. As of 2015, it was part of a display showcasing Prisoners of War in Canada and the Veterans Guard of Canada.

If you are interested in learning more about the history of Camp 100 at Neys, my recent article published in the Journal of Ontario History is now available to the public. It explores the history of Camp 100 from its origins as an internment camp for German combatant officers to a camp for Enemy Merchant Seamen and then finally its role in holding some of the most fanatic pro-Nazis in Canada. Click here to read it!

Still reading? If there are topics relating to POWs in Canada or the Veterans Guard that you are interested in and that you would like to see a blog post about, please leave a comment below!

Do you have a list of the camp guards at Espanola?

I’m afraid not as such lists don’t exist. Guards at internment camps did not have permanent postings, instead guard companies of about 250 men were rotated through different internment camps every few months. So there would be at least 1,000 different guards posted to Espanola every year, a few thousand over the course of its existence. If you’re looking for information about a specific guard, I’d recommend requesting their service file. More info on that here: https://powsincanada.ca/2017/05/23/requesting-canadian-wwii-service-records/