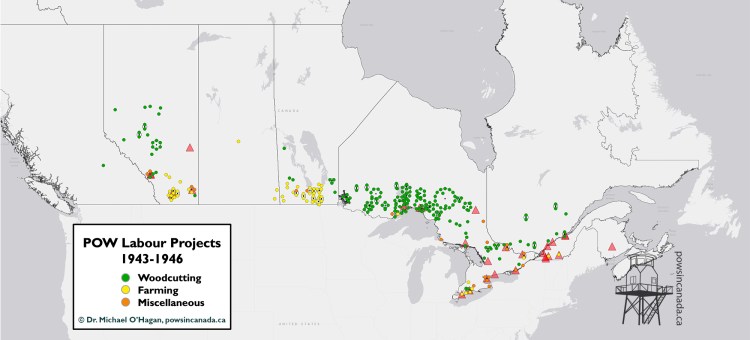

While the almost 35,000 Prisoners of War (POWs) – civilian internees, enemy merchant seamen, and combatants – were initially housed in large, traditional internment camps, the Department of Labour eventually employed over 16,000 POWs in almost 300 low-security labour projects scattered across the country.

In the early 1940s, with an steadily increasing number of young Canadians enlisting in the Armed Forces, Canada was faced with a severe labour shortage, particularly in the agricultural and lumber industries. In May 1943, after much debate, the Canadian government finally approved the Department of Labour to employ some of the thousands of young, able-bodied German POWs sitting idle behind barbed wire.

In order to test the feasibility of POW labour, the Department of Labour began a pilot program employing small groups of POWs from Camp 133 (Lethbridge) on local farms. A call for volunteers was issued and, with the promise of earning a wage, hundreds of POWs volunteered, most eager for the opportunity to work beyond the barbed wire confines of Camp 133. Working under armed guard, these POWs were primarily employed on sugar beet fields but also assisted in general farm work.

The success of the pilot program not only resulted in the expansion of POW farm labour in the Lethbridge area, but to much of Southern Alberta as well as Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Southwestern Ontario. Work generally remained seasonal, with POWs operating from temporary, tented hostels, between May and November.

With Canada in a nationwide firewood shortage in 1943, POWs were also employed in cutting fuelwood in Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. The Riding Mountain Park Project, more commonly known today as the Whitewater Lake POW Camp, in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, employed 440 POWs in a brand new camp to cut fuelwood to help relieve the province’s fuelwood shortage.

The pulp and paper industry, especially in Ontario, was also especially eager for POW labour to replace its civilian workers now in uniform. Thousands of POWs would work in the forests of Northwestern Ontario, Northern Alberta, and Quebec. Employed by civilian companies like Abitibi Power & Paper Co., Ontario-Minnesota Pulp & Paper Co., and the Pigeon Timber Co., POWs cut, hauled, and drove pulpwood down rivers in the spring. Camps were were rustic, with no running water or electricity, but had the advantage of having no barbed wire fences or guard towers surrounding them – only forest and a small guard force (approximately one guard per ten POWs). By providing POWs with relative freedom, the Department of Labour and the employers believed the POWs would be more likely to work harder. While POWs worked six days a week for $0.50 a day, they were able to spend their free time hiking and exploring, canoeing, and enjoying their surroundings.

The use of POW labour continued through 1946. Most of the logging camps were closed in the first half of 1946 as the POWs were transferred to the UK but POWs continued to work on farms in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario until November 1946.

Further Reading:

- O’Hagan, Michael. “Beyond the Barbed Wire: POW Labour Projects in Canada during the Second World War.” Doctoral Thesis, Western University, 2020. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6849.

- O’Hagan, Michael. “‘Freedom in the Midst of Nature’: German Prisoners of War in Riding Mountain National Park.” Forest History Today 23, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 56–62.

- Posts about Labour Projects

If you are interested in learning more about POW labour projects or are looking for information regarding a specific project, please contact me.

I would be interested in finding out more about the labour camp located in Turtle River park near Atikokan Ontario. Also if there were any camps in northwestern Alberta or Northeaster BC

Are there any remains of the three projects around Pine Falls? Living in the area I would be interested in taking a look, black flies and all!

I would be interested in what labor projects would be for the Farnham camp if you know. Thank you!