For thousands of prisoners transferred to Canada from places like the United Kingdom or North Africa, many arrived with little other than the clothes on their back. These uniforms were often the same that the prisoners had been captured in and were well worn or simply unsuited for Canada’s climate. While combatant prisoners were permitted to wear their military uniforms and decorations and Enemy Merchant Seaman could wear their seafaring uniforms, Canada still had to provide prisoners with clothing as needed.

Standing (left to right): Hellmut Meissner, Rupert Geiler, Hans Heck, Walter Meissner, Adolf Salamon, Erwin Rietze, Phillip Heinzelbecker. Seated: Erwin Gursch, Walter Hadamschek, Ernst Schwald, Otto Willie. Author’s Collection.

Article 12 of the 1929 “Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War” – more commonly known as the 1929 Geneva Convention – stipulated that detaining powers were required to provide suitable food, housing, and clothing to prisoners in its charge.

Clothing, underwear and footwear shall be supplied to prisoners of war by the detaining Power. The regular replacement and repair of such articles shall be assured. Workers shall also receive working kit wherever the nature of the work requires it.

Article 12, Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929

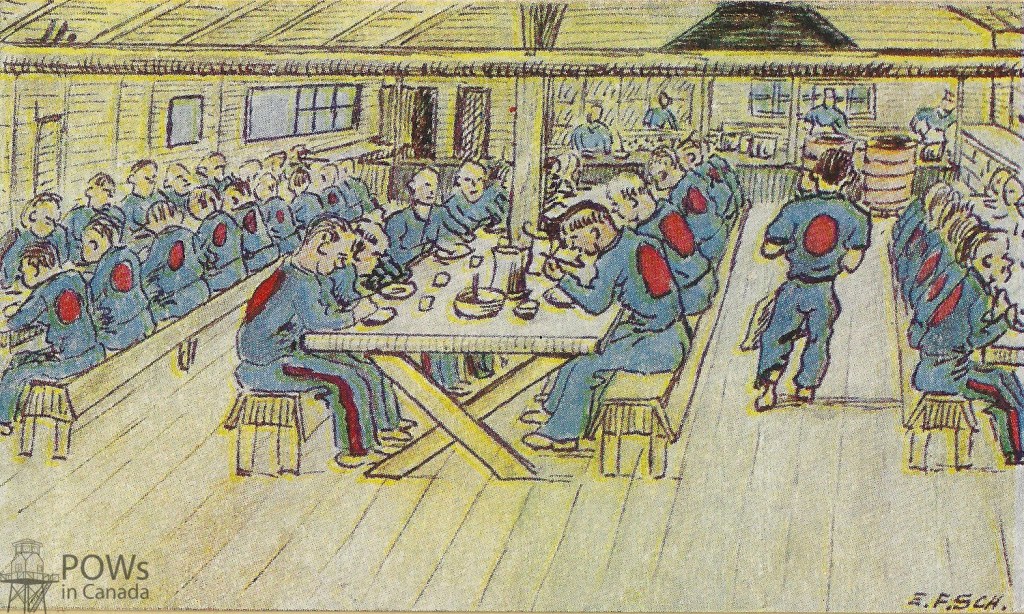

In procuring POW uniforms, the Department of National Defence not only had to provide uniforms suitable for Canada’s climate, but it was also in the interest of security that the clothing be clearly marked to identify the wearer as a prisoner of war. The British opted for clothing marked with large red or yellow circles, the United States would later mark all uniforms with large “PW” stenciled letters, but Canada adopted its own variation of a prisoner of war uniform.

The standard issue POW uniform was issued to civilian internees, Enemy Merchant Seaman, and combatant other ranks alike. It consisted of separate pieces for summer and winter and included a greatcoat or mackinaw, denim jackets and trousers, shirts, and peaked caps, all bearing distinguishing marks to identify the wearer as a prisoner of war.

The jackets and shirts featured a large red circle – measuring between 12 and 14 inches wide – on the reverse as a quick and easy method to identify a prisoner. The matching trousers had a 2- to 4-inch wide red stripe running down the right leg (and, sometimes, the left leg as well) while the caps had a large red patch along the top. In order to prevent prisoners from removing these distinguishing features, the red patches were not simply sewn on; instead, sections of the uniforms, whether it be the jacket’s circle or the trouser’s stripes, were cut out and replaced with red fabric, thereby making any modifications much more difficult.

As of 1944, each prisoner was provided with the following:

- Summer/General Issue

- 1 Pair of POW Boots

- 1 POW Summer Cap

- 2 Pairs of Cotton Underwear

- 1 POW Summer Jacket

- 1 POW Sweater Jacket

- 2 POW Shirts

- 2 Undershirts

- 2 Pairs of Socks

- 2 Pairs of Summer POW Trousers

- Winter

- 1 Pair Lumberman’s Boots

- 1 Winter POW Cap

- 2 Pairs of Wool Underwear

- 1 POW Mackinaw Coat or POW Greatcoat

- 1 POW Winter Jacket

- 2 POW Mackinaw Shirts

- 2 Wool Shirts

- 2 Pairs of Winter POW Trousers

- 2 Pairs of Felt Insoles

- 1 Pair of Leather Mitts

- 1 Pair of Wool Mitts

Worn out articles were exchanged while those working in labour projects, such as bush camps or farm hostels, received additional shirts, jackets, and trousers as needed.

The use of the POW uniform varied. While most civilian internees and Enemy Merchant Seaman appear to have adopted the uniform, combatant prisoners were much reluctant, instead preferring to wear their military uniforms. Prisoners joked that the red circles on their backs were targets for the guards to aim at in the event of an escape while others compared the red stripe running down the trouser leg to the red stripe worn by German generals.

I may not wear civilian cloths but only clothing with a red stripe. Perhaps you are able to send me a pair of navy trousers and a navy coat. That is a uniform and I may wear it. I don’t like to look like a parrot.”

Excerpt from letter from Horst Karschau, April 1944, Camp 130 Intelligence Report, LAC.

Replacement uniforms sent to Canada through the German Red Cross allowed these combatant prisoners to continue wearing their military uniforms while camp tailors busied themselves making the necessary repairs.

Officers generally refused to wear the POW uniform, instead preferring to wear their military uniforms. But under the Geneva Convention, officers were also responsible for purchasing their own replacement uniforms with their service pay so they had a bit more flexibility compared to their other rank counterparts.

For those working outside the camp, either on a day-to-day basis or while living in a bush camp or farm hostel, the POW uniform was the preferred choice. While some labour projects allowed prisoners to wear their military uniforms, most of these men elected to reserve them for special occasions and instead adopted the better-suited POW uniform.

As shipments from the German Red Cross curtailed in 1944 and 1945, the prisoners were no longer able to find replacement uniforms and, following Germany’s surrender in May 1945, there was less reluctance to wear an enemy’s uniform. More and more POWs began using the POW uniform as their daily attire although some continued to wear their military uniforms – although regulations stipulated the Nazi insignia now had to be removed.

By 1946, Canadian manufacturers had produced thousands of jackets, shirts, caps, and other pieces of apparel. After the last prisoners left Canada for the United Kingdom in 1947, the Department of National Defence now found itself with thousands of surplus POW uniforms. Like most surplus equipment, the clothing was eventually turned over to the War Assets Corporation for disposal. In the years following the end of the war, POW shirts, jackets, trousers, and caps could be found on the surplus market.

In order to make them less conspicuous and more appropriate for post-war use, many articles of POW clothing were modified by removing or covering the red swatches, stripes, and circles that once identified the wearer as a prisoner of war.

The well-used jacket seen above was one of many jackets converted post-war for civilian use by adding a swatch of fabric on the reverse to cover the red circle. Removing the swatch reveals a pristine red circle, suggesting the jacket was unused surplus before it was converted for civilian use.

Likewise, this cap is the same model as the example shown earlier but the red stripe has been covered with the same denim fabric used to make the rest of the cap. Inside, the red fabric is still clearly visible stamped with the “C Broad Arrow,” indicating Canadian government property, and the War Assets Corporation mark, indicating it was surplus.

Despite the significant number of surplus uniforms, few articles have survived. Most were well used in the post-war years and discarded while a handful of pieces have made it into the collections of places like the Canadian War Museum and the Glenbow or in private collections.

To learn more about POW uniforms and to see other examples of clothing worn by prisoners in Canada, check out the link below. This is the first in a new series of pages that explores life in Canada’s internment camps.