When Otto Ellmaurer arrived in Kananaskis, Alberta in July 1940, the forty-one year old was not there to admire the majestic Rocky Mountains. Instead, he was a prisoner of war, a civilian internee detained as a potential threat to national security and he would spend almost five years behind barbed wire. To help pass the time at Camp K, he turned art, producing the “Kananaskis Record,” a collection of humourous cartoons documenting life in Canada’s first internment camp of the Second World War.

Born in Sontheim, Germany in 1899, Joseph Otto Ellmaurer left Germany in 1929 with his brother, Anton. They settled in Montreal and although Otto had a background as a merchant, he found employment as a draughtsman. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Canada began interning German civilians deemed a threat to national security and, among them, was Otto Ellmaurer. It is unknown why Otto was flagged as a potential risk but he was arrested by the RCMP sometime in Fall 1939. Ellmaurer was transferred to the receiving station Fort Henry before arriving at Camp P near Petawawa in December 1939. Then, in July 1940, Ellmaurer was one of 150 internees transferred to Camp K at Kananaskis.

Camp K was Canada’s first internment camp of the Second World War when it opened in September 1939. While the camp was originally built to hold internees from Western Canada, construction delays at Camp P at Petawawa and a later shuffling of internment camps meant Kananaskis would eventually hold German civilian internees from across the country.

At Kananaskis, Ellmaurer began work on his “Kananaskis Record: Humoristische erlebnisse – Hinterm Drahtverhau – Konzentration” (Kananaskis Record – Humorous Experiences Behind the Wire), a series of prints documenting and, often mocking, life at Camp K.

The cover image shows an internee asleep in the bunk wearing the standard POW uniform. Strands of barbed wire fence can be seen through the window while personal items – a calendar, photographs, and handicraft – adorn the prisoner’s space. A pet dog sleeps beside the bed and a crow (or raven?) sporting crutches – the story behind this is unknown – looks on. The scene is surrounded by several squirrels, two of whom are even sporting their own tiny POW caps.

One of Ellmaurer’s better-known sketches, “Join the Nazis and See Canada,” adapts the common recruiting phrase, “Join the Army/Navy and See the World,” to the internee experience. “Montreal, Toronto, Kingston, Petawawa, Kananaskis, Fredericton, — ?” described Ellmaurer’s own journey as an civilian internee; after being detained in Montreal, Ellmaurer was likely moved through Toronto to the receiving station at Kingston’s Fort Henry before he was interned in Camp P at Petawawa, Camp K at Kananaskis, and, later, Camp B near Fredericton. The “?” ends the list as the internees were never sure where they would be transferred next. Note the armed guards escorting the prisoners and the trailer full of “souveniers” from the internees’ travels.

Arriving in an internment camp was a significant adjustment. Thrust into a military environment, internees had to quickly adjust to living under someone else’s rules or face the consequences.

Parades were common occurrences in camp, with roll calls taken every morning and evening and parades for being sick and injured as well as those willing to work. But, as this cartoon hints at, organizing internees at Kananaskis and other camps came with its challenges as these men were civilians and many had no military experience. Not to mention that disrupting parades or ignoring the guards’ orders were among the few forms of resistance prisoners could take towards their captors.

Breakfast was served after morning roll-call and feeding hundreds of internees was no mere task. Cooks and kitchen helpers – all internees – they had to provide three meals a day to all prisoners in camp (the guards and camp staff had their own kitchen staff). Here, the head cook, “Leo” and his kitchen “artists” prepare a meal while two hungry POWs look on through the kitchen window.

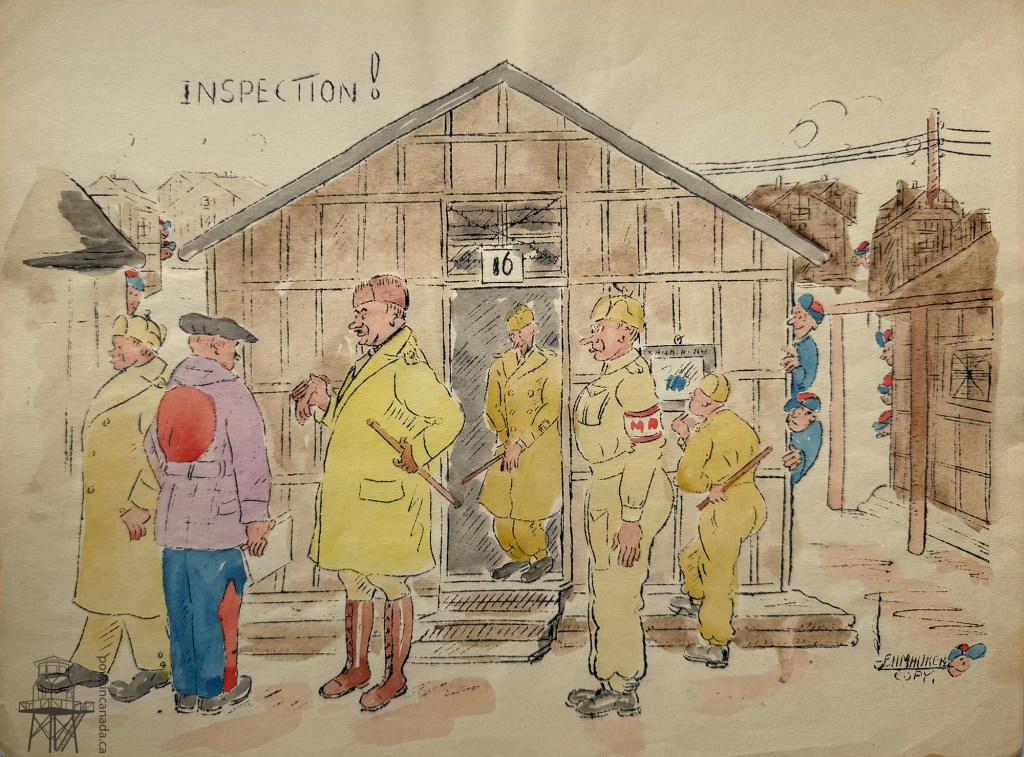

Guards regularly conducted hit inspections to ensure the internees’ quarters remained neat and tidy and to keep an eye out for any signs of escape, sabotage, or illicit activity in camp. Signs of tunneling or the possession of homemade alcohol, weapons, escape supplies, or other illicit articles could land a prisoner up to twenty-eight days’ detention.

Here, Camp Commandant Lt.-Col. Hugh De Norban Watson (in the brown cap) speaks with Camp Spokesman Johannes Brendel, the internee in charge, in the purple jacket. Note the prisoners peering around the corner, no doubt waiting to see what the guards did – or did not – find.

With nothing but time on their hands, prisoners engaged in a variety of activities including music, theatre, handicraft, and, obviously, art. The prisoners gathered together a small orchestra under the direction of internee Erich Kaunat.

Kaunat, a Montreal resident, had conducted a small orchestra before the war, while the orchestra would have been a mix of professional and amateur musicians. Instruments were often provided by international aid organizations like the War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Outside of recreation, work opportunities also helped prisoners pass the time while offering them an opportunity to earn a small wage. Camp staff arranged for small groups of prisoners to engage in various types of work; at Kananaskis, most of these groups were employed in cutting firewood to feed the camp’s many wood stoves during the winter months.

While prisoners greatly valued the ability to leave the barbed wire confines of camp, albeit briefly, work parties also offered the temptation of an easier escape, as Ellmaurer makes clear here.

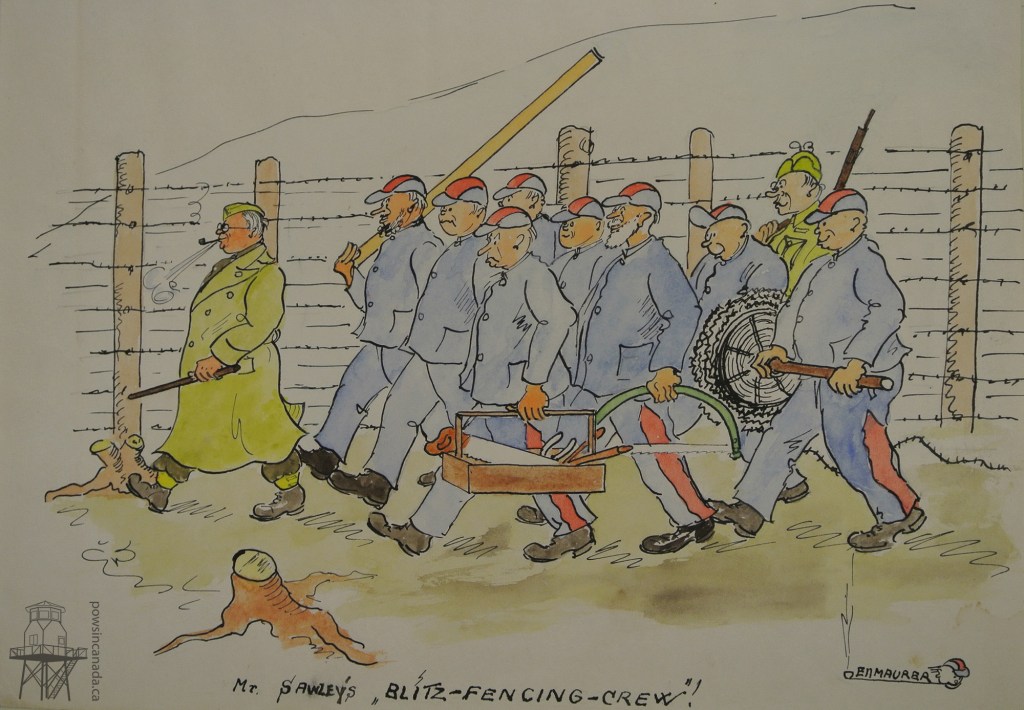

Examples of Ellmaurer’s sketches in the Glenbow Collection at the University of Calgary show Ellmaurer produced a few others apart from his Kananaskis “souvenirs”. Among material donated by Captain Herbert Sawley, a guard officer at Kananaskis, were two examples of Ellmaurer’s art. Both depict a “Blitz-Fencing-Crew” led by a then-Lieutenant Sawley (wearing glasses and a greatcoat).

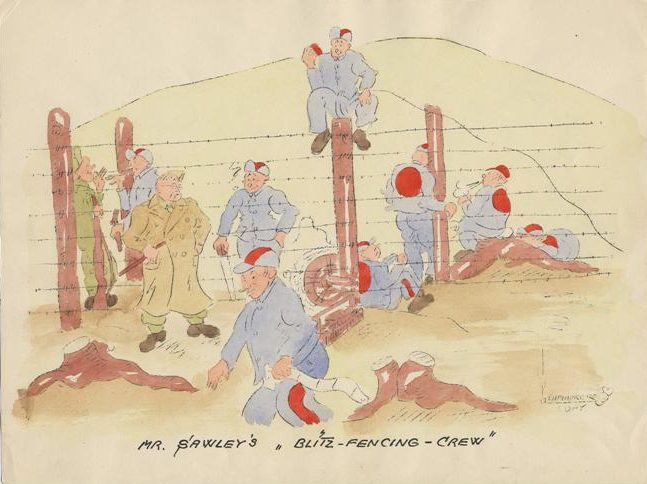

It was not uncommon in earlier internment camps to have working parties build barbed wire fences as the camps expanded or layouts changed but Ellmaurer’s sketches raise questions about the effectiveness of these parties; while the prisoners look all business on their way out to the site, their arrival suggests anything but.

Rather than building the barbed wire fence, the prisoners are seen goofing off much to Sawley’s chagrin. One prisoner chats with a guard, one heads off to the bush with toilet paper in hand, another sits on top of a post with a stand of barbed wire in one hand and an apple in another, while the rest smoke or nap. So much for Sawley’s “Blitz-Fencing-Crew”!

It is unknown how many copies of the these prints were produced but surviving examples remain unique due to their hand-colouring. Consider the example show above with the three seen below. Notably, the one gifted to Captain Sawley appears to have been done with more care and has been outlined in greater detail.

Adding colour appears to have been done either by Ellmaurer or other prisoners as some copies, such as most of those seen here, are seen in full colour while other copies are limited to outlines or highlights.

Check back next week as I take a look at more of Ellmaurer’s art in Part II of Kananaskis Cartoons. Be sure to sign up for email notifications at the link at the bottom of the page. If you need something to tide you over until next week, check out the history of Camp K by clicking the link below.

And a special thanks to Martin for rescuing these and a few other pieces from the garbage!

March 25, 2025 – the second part of this post can be found by clicking the link below.