February marks Black History Month in Canada, an opportunity to learn more about the history of Black Canadians.

George Alexander Downey was forty-eight years old when he stepped foot in a Halifax-area recruiting office to enlist in the Canadian Army. Like most of the men his age, Downey had served in the First World War but his service was different than most; he was a Black Canadian veteran of the No. 2 Construction Battalion. Despite having served in a segregated battalion and enduring continued discrimination in the First World War, Downey was among a small group of Black Canadians veterans who enlisted in the Veterans Guard of Canada. Although the Army was no longer segregated and they no doubt hoped for better treatment this war, Black Canadians serving in the Veterans Guard would soon discover racism and discrimination would once again shape their military service.

Several thousand Black Canadians volunteered for military service in the Second World War, serving in places like Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Among these volunteers were a small number of First World War veterans who once again answered their country’s call. Some, like George Downey, had served in Canadian battalions like the No. 2 Construction Battalion while others had served in British units, including the British West Indies Regiment, before settling in Canada after the war. Now in their late forties or early fifties – too old for overseas service – these men joined the Veterans Guard of Canada.

Originally established as a home defence force, the Veterans Guard of Canada quickly took responsibility for guarding and administering prisoners of war (combatants and non-combatants) interned in Canada. The Corps was organized into guard companies of roughly 250 men with each company rotating through different postings every one to six months, alternating between training, guard duty at internment camps (and, later, labour projects or work camps), guarding military installations, and manning coastal defences. While Black veterans now expected to stand shoulder to shoulder with their comrades, in 1941, their war would change.

In June 1941, a Quebec-raised company of the Veterans Guard was guarding German officers at Camp F (Fort Henry). Among the company’s ranks were three Black Canadian soldiers and, like their comrades, these men were tasked with patrols, manning guard posts, and escorting prisoners. That is until Nazi officers in camp voiced their racist views; Major-General Georg Friemel, the ranking prisoner in camp, requested the Camp Commandant transfer the three Black soldiers elsewhere, stating, “The German Officers feel that it is not right to place them under guard of coloured troops.”1 While Friemel did not lodge an official protest, then Director of Internment Operations, Colonel Hubert Stethem, considered it “advisable” to transfer the three guards to other duties to avoid trouble. The guard company happened to be transferred to Montreal before for a final decision could be made but the incident would set the stage for the coming months.

Shortly after Friemel’s complaint, the German government protested the use of Black soldiers to guard German officers in Great Britain and the Commonwealth, threatening reprisals against Allied prisoners in Germany if the practice continued. As Germany had more Allied prisoners in custody than the Allies had German prisoners, the British government remained extremely reluctant to enact any policy or practice that could endanger the lives of its own soldiers. And with Canada holding several thousand prisoners for Great Britain, British policy had direct implications for Black Canadians serving in the Veterans Guard.

Although the Department of National Defence never gave an official order, camp commandants were advised to “use discretion” when employing Black Canadian guards or camp staff and instead recommended these men be employed in duties other than guarding or escorting German POWs. With this policy remaining off the record, it is unknown how many officers relegated Black Canadians to other duties but most Black guards were quietly – and without explanation – assigned to other, less visible duties within the Veterans Guard. Many, including Privates George Downey and F.A. Clarke became Batmen (serving as an orderly, runner, or officer’s assistant), while at least one, Sydney Flood, was assigned as a Weapons Instructor.

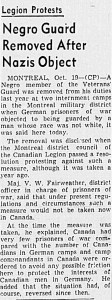

The unofficial policy did not go unnoticed. As most of these veterans were Legion members, word soon spread and, in March 1942, the Montreal District Council of the Canadian Legion protested the Department’s decision and forwarded the matter to Legion Headquarters. The story received some attention in newspapers across the country, prompting several Legion branches to follow suit and request an investigation into the matter to ensure it did not happen again.

A subsequent review revealed Colonel H.R. Alley, Officer Administering of the Veterans Guard, was not consulted in the Department of National Defence’s decision. He strongly opposed the matter, arguing Canada’s army had no colour line and that such a policy should not be made “at the demand of any foreigners, whether prisoners of war or not.”2

In my opinion Canadians, regardless of race, colour or creed, are on equal footing and should remain so.

Colonel H.R. Alley, July 14, 1941, HQS 7236-37, C5387, RG24, LAC.

Alley also expressed concern that this policy would prompt the German government to only increase its demands and target indigenous soldiers serving the Veterans Guard next. Despite Alley’s opposition, the investigation made little progress and the discriminatory practice remained in place at several POW camps. That is, until 1944.

In late November 1944, Private Cornelius McKenzie was among sixty guards transferred to Camp 44 (Grande Ligne) as reinforcements. McKenzie, Jamaican-born and a veteran of the British West Indies Regiment, had settled in Montreal in the interwar period and, along with Dominique François Gaspard, had become a founding member of the the Coloured War Veterans’ Legion (Quebec Legion Branch No. 50). After arriving at Grande Ligne, McKenzie was promptly removed from guard duty without an explanation – the second time in as many years. Upon returning to his company, he promptly paraded himself in front of his Commanding Officer to demand an answer. Assuming he had been relieved of his duties because of the colour of his skin, McKenzie declared that unless the situation was rectified, he would not only demand his own discharge on the grounds of discrimination but that of his two sons serving in the Canadian Army overseas – one of whom had just been seriously wounded fighting in Normandy.

McKenzie’s persistence finally prompted change. In January 1945, the Department of National Defence issued a statement clarifying – and reversing – the discriminatory policy. In a letter to all military districts, Major-General A.E. Walford explained that the policy had come from an attempt to prevent reprisal action against Allied prisoners in Germany but, considering Allied countries now had more German POWs, Black Canadian soldiers serving in the Veterans Guard were to resume their normal duties.

Finally able to serve as guards, most of these men would remain with the Veterans Guard for the next year. George Downey, who had spent almost four years as a batman with No. 18 Company, spent January training in Sherbrooke, Quebec, before he and his comrades were moved to Camp 44 (Grande Ligne). Despite the presence of strong Nazis here, there are no records indicating any complaints from the prisoners there this time. Downey was later transferred to Camp 70 (Fredericton) before he receiving his discharge in August 1945. He returned to his wife and children in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

While the exact number of Black Canadians serving in the Veterans Guard is not known, these men once again carried out their duties in service of their country despite discrimination. Most had no doubt hoped for a better outcome than their service some thirty years prior but this was not necessarily the case. But thanks to the persistence of soldiers like Cornelius McKenzie, Black Canadians were finally permitted to serve in the role they had volunteered for almost five years prior.

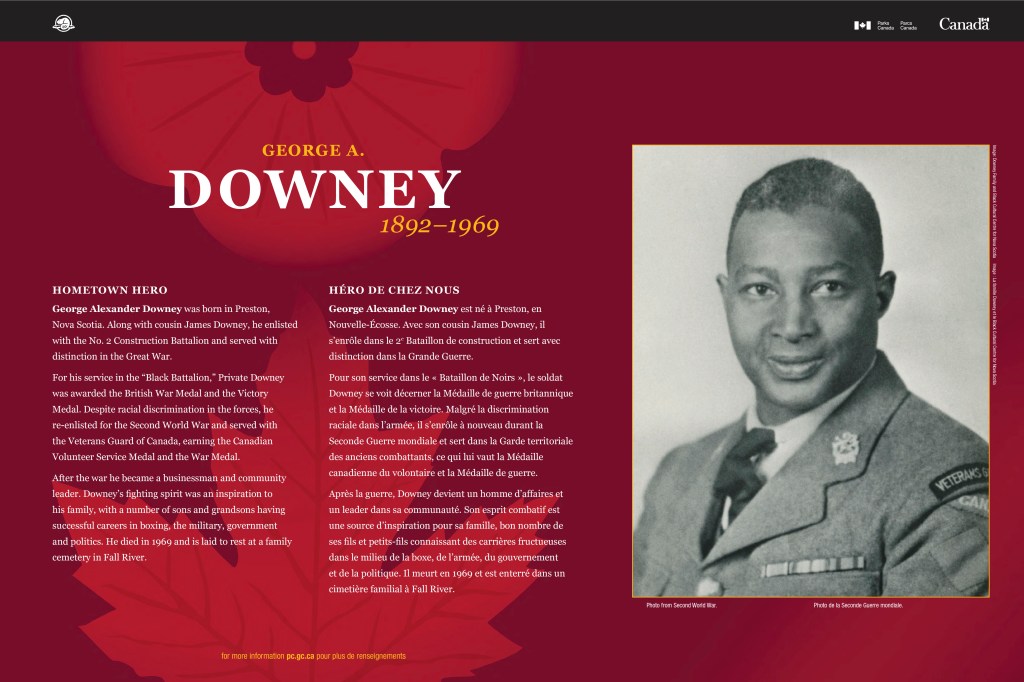

In recent years, the stories of the men who served with the No. 2 Construction Battalion have finally come to light. George Downey, for example, was recently recognized by Parks Canada as part of the “Hometown Heroes of Nova Scotia.” However, like the rest of the men who served with the Veterans Guard, their contributions in the Second World War have often been overshadowed by their First World War Service. As interest in the Canadian Homefront grows, hopefully the dedication of these men serving in both world wars can be recognized.

To learn more about Black Canadians in uniform, visit BlackCanadianVeterans.com or follow them on Facebook.

Thank you to the Downey family for their help sharing George’s story.

thanks for fine informative piece with solid context and information.

Dieter K Buse