In the early hours of April 19, 1941, Private C. Gordon of No. 2A of the Veterans Guard of Canada was manning one of five guard towers surrounding the enclosure of Camp X at Angler, Ontario. Alone in the tower’s lookout, Gordon was keeping watch on some 560 German prisoners of war when he heard movement somewhere behind the tower. Suspicious, he reported the sound to his superior, Corporal Keegan, and the pair began searching the area. Within minutes, they made a troubling discovery: what appeared to be the exit of a tunnel coming from the direction of the enclosure. Although they did not yet know it, Gordon and Keegan had just uncovered the largest escape attempt from a Canadian prisoner of war camp during the Second World War.

Located about five kilometers from the present town of Marathon, Camp X at Angler was one of the first two purpose-built internment camps in Canada. Along with Camp W at Neys, Camp X was established to hold German combatant prisoners transferred from the United Kingdom for safe keeping, with Neys designated for German officers and Angler for other rank POWs.

The camp’s enclosure included four H-Huts serving as the prisoners’ barracks as well as a kitchen and mess, recreational hall, tailor’s workshop, detention hut, and small hospital. This was all surrounded by a warning wire, two layers of barbed wire fences, and five guard towers constantly manned by the men from the Veterans Guard of Canada. Outside the enclosure were quarters and messes for the camp staff and guard and other facilities necessary for an internment camp, including a guardhouse, administration building, supply depot, and larger hospital.

The 560 prisoners had arrived at Camp X in late January 1941. The majority were Luftwaffe crews shot down during the Battle of Britain and, having only just arrived from the United Kingdom, they had complete faith in a German victory. Despite their status as prisoners, many were keen to remain active participants in the war and the best way to do so was to escape.

It was time to escape, to escape from this camp; not, because the treatment is bad, but because we are German soldiers, we love our country like any other soldier of any nation.

Horst Liebeck, “The way to Freedom,” April 29, 1941, HQS 7236-80-101 – Treatment of Enemy Aliens – Courts of Inquiry – Camp 101 Angler, C5397, RG24, LAC.

The prisoners were well aware that their odds of reaching Germany were slim at best but escape wasn’t just about going home; properly executed, a mass escape would tie up Canadian military personnel and supplies that were desperately needed overseas. In the event escapees succeeded in evading capture, the United States was still neutral country and, with the help of German sympathizers, a prisoner who succeeded in crossing the border could indeed have a chance of making it home. So, almost immediately after arriving at Angler, a group began plotting their escape.

In the following weeks, planners evaluated their options while others gathered supplies and tools. Escape by tunnel was deemed the most feasible option and the prisoners began tunneling under one of the barracks, cleverly concealing the entrance under the floorboards. Using homemade trowels and small shovels, the prisoners began dug their way through the sandy soil, repurposing floor joists to support the tunnel walls and building an improvised ventilation system to move fresh air to those toiling below the surface.

By mid-April, the tunnel was complete and the escape was planned for the night of April 18-19 to roughly coincide with Hitler’s birthday. In the nights leading up to the escape, several prisoners slipped out of the camp through the tunnel and hid food and supply caches in the surrounding area to reduce the supplies needed to be carried by the escapees.

In the evening of April 18, after the guards conducted their nightly roll call, the prisoners began their escape. Equipped with knives, homemade compasses, maps, food, blankets, and extra clothes, the first prisoners made their through the small tunnel. Under the cover of darkness and helped by poor weather, they began exiting the tunnel around 9:30 p.m. For the next three hours, the prisoners slowly slipped out of the camp one by one until one of the prisoners apparently tripped, alerting Private Gordon in his tower. But by the time Gordon and Keegan discovered the tunnel, twenty-eight prisoners had escaped into the darkness.

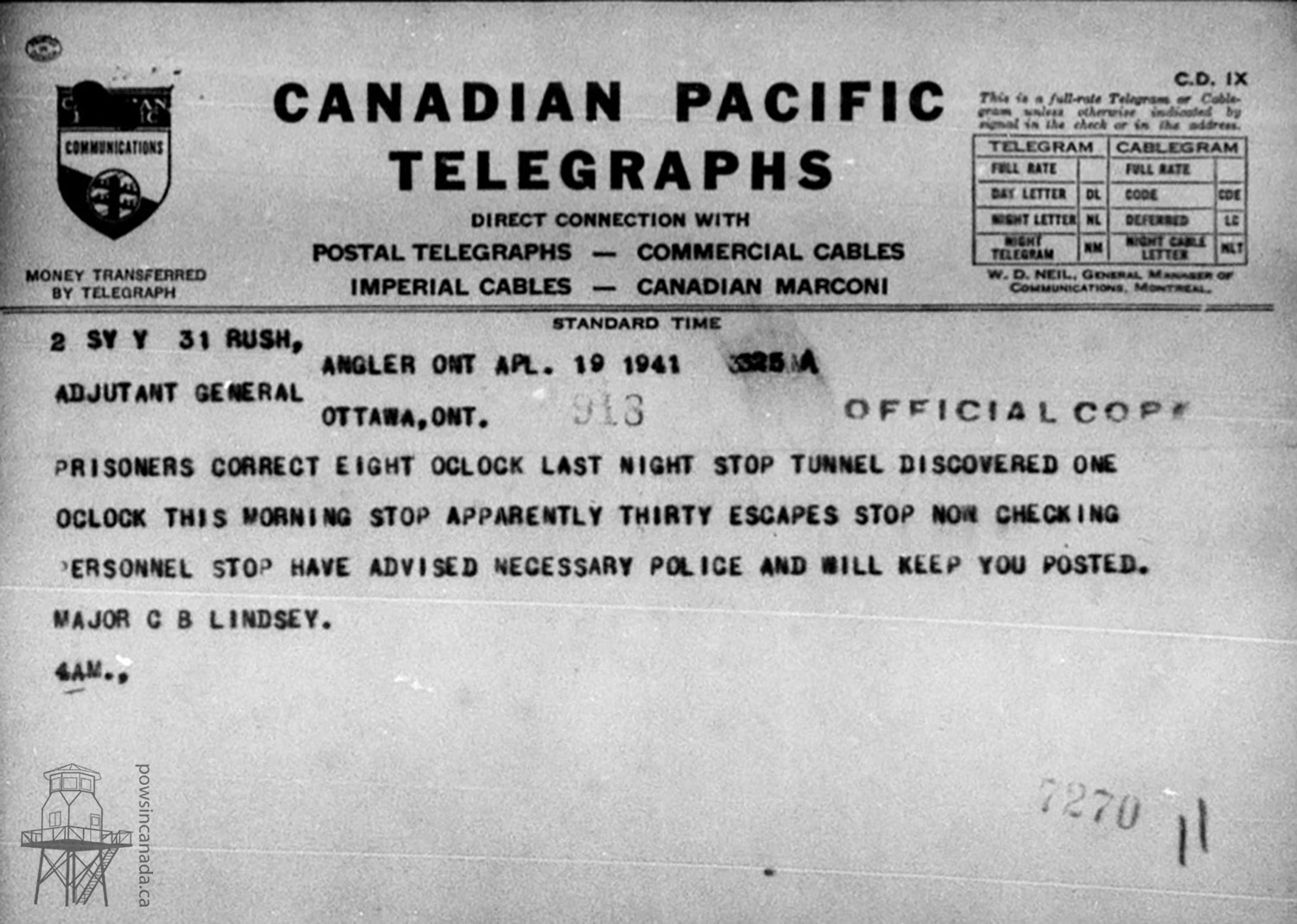

The alarm was quickly raised and the guards and camp staff immediately put the camp’s escape plan into action. Sentries and patrols were dispatched to predesignated locations throughout the surrounding area while a count of the prisoners was made in the enclosure. A search of the prisoners’ huts revealed several beds with dummies in them and it was not until the early morning that the camp staff realized approximately thirty POWs were missing.

Patrols found two of the missing prisoners not far from the camp but considering the size of the escape, the Camp Commandant called upon help from the Algonquin Regiment stationed in nearby Port Arthur. Fifty soldiers and officers from the Ontario Provincial Police and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police were soon on their way while local indigenous men were brought on as trackers and, with their intimate knowledge of the area and its cabins, shacks, and shelters, began guiding patrols through the dense bush.

Later that morning, one of the trackers spotted smoke and led a patrol to a small cabin in the bush. Suspecting there were POWs inside, Veterans Guard Sergeant T. Ridgway ordered the occupants to come out but before he could finish speaking, the door burst open and Ridgeway was knocked to the ground. Prisoner Oskar Broderix made a break for the trees but one of the other guards opened fire, almost shooting Broderix’s nose off. Broderix and three other prisoners hiding in the cabin promptly surrendered.

By the end of the first day, April 19, patrols recaptured eleven of the twenty-eight missing prisoners had. Each prisoner was well-supplied with food, clothing, and detailed maps of Canada and the United States – evidence of a well-planned escape.

The search for the missing prisoners had also revealed several food caches hidden in nearby huts and cabins. One of these caches, tucked away in a small shack, was left as bait and a patrol from the Algonquin Regiment was posted nearby to keep watch. The tactic succeeded for, in the early hours of April 20, Sgt. Davies and Pte. Saunders discovered five prisoners sleeping in the shack. Davies ordered the prisoners to surrender and but no one emerged. The pair could hear some movement inside so Davies repeated his order. Suddenly, one of the prisoners, Erwin Genssler, burst through the hut’s door and Davies and Saunders, believing they were about to be overrun, opened fire on the shack. As instructed, they purposely aimed low so as not to kill the prisoners but Genssler never approached the soldiers, instead making a break for the tree line. Davies fired upon the fleeing prisoner, who promptly dropped to the ground.

After the rest of the patrol caught up, runners were sent back to report the incident and bring help. By sheer luck, Erwin Genssler, the prisoner who had tried to run, was uninjured but his four comrades were not so lucky. Although the soldiers had purposely aimed low to avoid inflicting serious injuries, most of the prisoners were still lying down when the shooting began and all four were struck by bullets; Hans Hauck escaped with minor injuries, Kurt Rochel was seriously wounded, while Herbert Löffelmeier and Alfred Miethling both succumbed to their injuries.

Later that evening, a patrol searching near Heron Bay recaptured three more prisoners hiding in an empty boxcar. Then, the following morning, a railway sectionman found another three prisoners also in the vicinity Heron Bay, leaving only six prisoners still on the run.

Back at Camp X, a search of the tunnels and the POW barracks revealed four small boats each capable of holding three men, a small railway built to move supplies and the boats in the tunnel, and more packs containing food, homemade knives, rope, and wire. In all, the prisoners had some 300 lbs of meat packed in jam jars, 225 lbs of bacon, 120 lbs of cheese, thirty loaves of bread, 181 cans of milk, and other assorted foodstuffs. Judging by the supplies seized, authorities believed another twenty-two prisoners were scheduled to escape had the attempt not been thwarted.

As engineers destroyed the tunnel with explosives, patrols continued their search for the missing prisoners. No sign came for the next two days but then, on April 24, camp staff received an unexpected telegram; RCMP officers had just arrested two of the missing prisoners in Medicine Hat, Alberta – a 2,000 kilometre journey from Camp X. After emerging from the tunnel, Horst Liebeck and Karl-Heinz Grund had followed the rail line near camp to the next station where they knew a train was set to arrive at 1:00 a.m. Their goal was to make it to Vancouver where they would hop aboard a ship headed to Japan or Russian – neither of which had joined the war – and then back home to Germany. The train arrived on schedule and the pair were soon on their way to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay). There, posing as foreign vacationers, they boarded a passenger train, and arrived in Winnipeg two days later. After spending some time there – eating at a hotel and taking in a movie – the pair continued their journey westward, arriving in Alberta on the 24th. But there, one day away from Vancouver, their luck ran out. The police arrested the pair and they were soon on their way back to Angler.

The final four prisoners – Helmuth Ackenhauser, Willi Bauer, Wilhelm Erdnis, and Hans-Georg Schulte – continued to evade their pursuers but their bid for freedom would come to an end on April 25. Patrols captured the men near Heron Bay, finally ending the six-day manhunt.

With all the prisoners accounted for, authorities launched an investigation into the escape and the events that led up to the shootings of the escaped prisoners. The conclusions were that the soldiers were justified in their use of force and had followed all precautions to wound, rather than kill, the escapees. But the investigation also revealed serious shortcomings with security measures in Canadian internment camps and prompted changes in policies and precautions that would remain in effect for the duration of the war, including better lighting of the enclosure and fence lines and to have guards routinely search and probe for tunnels.

As for the prisoners, they returned to Camp X for the time being. The three injured men – Hauck, Rochel, and Broderix – would all recover from the wounds while Herbert Löffelmeier and Alfred Miethling were laid to rest by their comrades in a small cemetery not far from the camp. Hand-carved markers adorned the graves and the prisoners tended to the cemetery for the duration of their stay (the bodies were later moved to Thunder Bay’s Riverside Cemetery after the war and then to Kitchener’s Woodland Cemetery in the 1970s). The last German POWs left Angler in May 1942 and the camp, now renamed Camp 101, was repurposed to house Japanese-Canadian internees from British Columbia.

The escape from Camp X in April 1941 was only one of many escapes from Canadian prisoner of war camps. Some were successful but the vast majority were not. But, as the Angler escape demonstrated, it wasn’t just about returning home. Prisoners escaped for a variety of reasons: to do their duty as soldiers and to “fight” against their enemy, to protest their treatment, to get transferred to another camp, to stay busy and help pass the time, to get some excitement in their lives, or even as a way of staying in Canada rather than return to Germany. For prisoners like Horst Liebeck, one of the POWs who made it to Medicine Hat, there were no hard feelings against his captors; in his statement following his recapture, he concluded,

Both our countries will live in peace, where we can take a free speech as gentlemen to gentlemen, not as enemy to enemy. That is our greatest wish.

Horst Liebeck, “Horst Liebeck, “The way to Freedom,” April 29, 1941, HQS 7236-80-101 – Treatment of Enemy Aliens – Courts of Inquiry – Camp 101 Angler, C5397, RG24, LAC.

I respect everybody who tries to escape, because this is a brave deed for his country, everbody, if German or English or anyone.

The Twenty-Eight:

- Fw. Helmuth Ackenhausen – Captured April 25, 1941

- Ofw. Willi Bauer – Captured April 25, 1941

- Fw. Oskar Broderix – Captured (Wounded) April 19, 1941

- Uffz. Kurt Eiselt – Captured April 19, 1941

- Fw. Wilhelm Erdnis – Captured April 25, 1941

- Fw. Heinz Ettler – Captured April 19, 1941

- Ofw. Hermann Frischmuth – Captured April 20-21, 1941

- Ofw. Erwin Genssler – Captured April 20, 1941

- Ofw. Karl-Heinz Grund – Captured April 24, 1941

- Gefr. Hans Hauck – Captured (Wounded) April 20, 1941

- Uffz. Philipp Hess – Captured April 19, 1941

- Flg. Wolfgang Koehler – Captured April 20-21, 1941

- Maat. Waldemar Lessman – Captured April 20-21, 1941

- Fw. Rudolf Lichtenhagen – Captured April 19, 1941

- Gefr. Horst Liebeck – Captured April 24, 1941

- Gefr. Herbert Löffelmeier – Killed April 20, 1941

- Gefr. Alwin Machalett – Captured April 20-21, 1941

- Gefr. Alfred Miethling – Killed April April 20, 1941

- Ofw. Alfred Petzka – Captured April 19, 1941

- Fw. Wilhelm Raab – Captured April 19, 1941

- Gefr. Rudolf Riemer – Captured April 19, 1941

- Ofw. Kurt Rochel – Captured (Wounded) April 20, 1941

- Fw. Erhard Scheidt – Captured April 19, 1941

- Fw. Hans-Georg Schulte – Captured April 25, 1941

- Ogefr. Willi Steube – Captured April 20-21, 1941

- Ofw. Paul Steutzel – Captured April 20-21, 1941

- Ofw. Horst Streit – Captured April 19, 1941

- Uffz. Georg Wolff – Captured April 19, 1941

Thanks for th